Alexander Twilight was Black. Then he was white.

That comical statement is the truth of Twilight’s identity according to the 1800 and 1810 US Censuses. You may be asking if this change was arbitrary or justified by a significant change within that decade. The answer? Well, both.

Marina Affo gathered a lot of relevant information on Twilight from Middlebury College scholars Daniel Silva and Bill Hart. Among the crucial facts in this race conundrum includes the death of Twilight’s father, a mixed yet visibly Black man, sometime between 1800 and 1810.

The presence of Twilight’s Black father is what gave the state of Vermont confidence to list Twilight as a free Black person in the 1800 census. Back then, census taking was a door-to-door hustle like many things were. With Twilight’s father gone by 1810, there were no Black descendants for the next census taker to connect the white-passing Twilight to.

As far as the state of Vermont was concerned, Twilight was now white.

Twilight’s change in racial identity was both reasoned and random. But as this piece of historical trivia shows, the “reason” in racial categorization is set on a wobbly foundation of fear.

You are what we say you are…you know, so we can hoard resources

Race in America defaults toward “other,” keeping as many people away from the dominant racial identity as possible. This belief was later cemented by the one-drop rule in the 20th century. This “othering” away from whiteness is weird, globally speaking.

As long as you’re a citizen and say nothing of race, people in France are quick to be accepted as “French.” Put a light-skinned and a dark-skinned Brazilian side by side, and a fellow countryman would say they are both just “Brazilian.” This is hyperdescent. Most nations let as many people into the default group as possible because they want to avoid the racial tension that the United States intentionally creates.

Hyperdesecent says, “we really want you to be one of us!” Even if racist oppression is rampant, a society set up by hyperdescent wants to make inclusion as easy as possible.

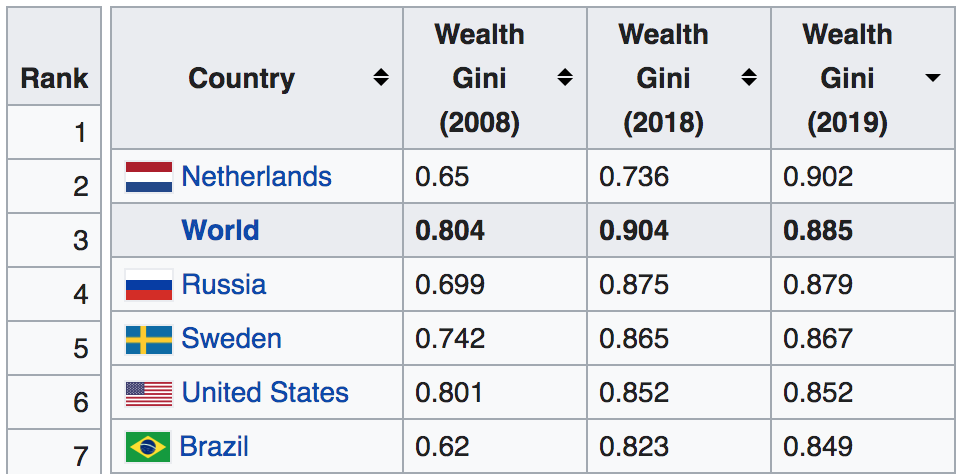

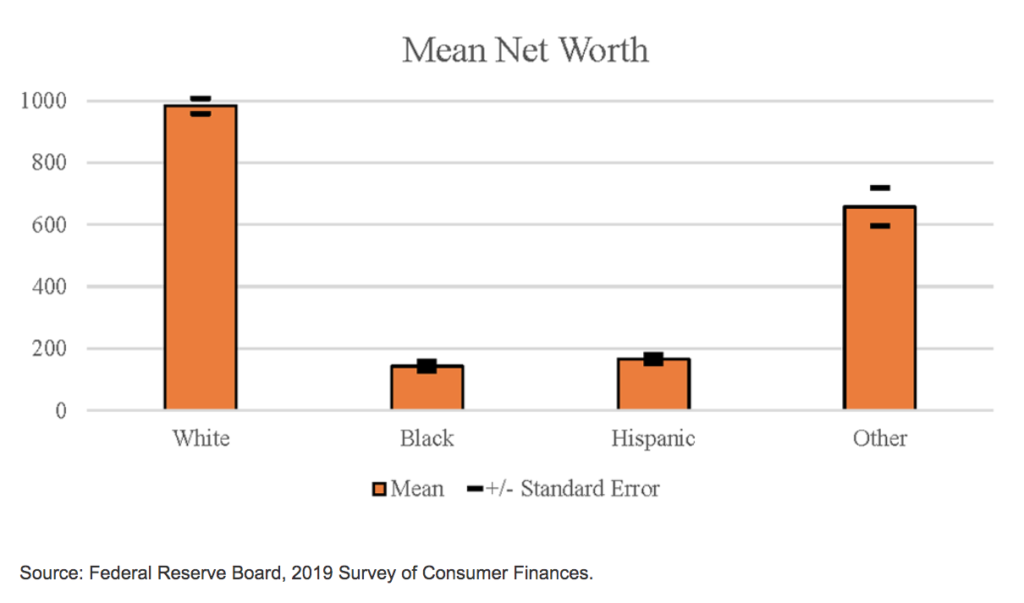

The racial realities of other societies make the idea of “white-passing” despite being mostly white a strangely American thing. Once you see the nation’s distribution of wealth, you get a good sense of why it does that.

Race in the U.S. is commonly understood through the one-drop rule: traceable and “recent enough” lineage to a non-white person determines your race. This is hypodescent. Hypodescent says, “We’ll do anything to make sure you’re not one of us.” It encourages intense cultural assimilation and, quite frankly, the need for a fixed group at the bottom to shit on.

A society based on hypodescent makes inclusion as difficult as possible. Meanwhile, it teaches you to love the fight for inclusion to distract from the impossibility of inclusion. In practice, hypodescent in America has only strongly applied to Black Americans.

Upon having mixed children with white partners, Asian and Latinx identities can disappear into whiteness as soon as two generations later. This has never been the case for Americans with traceable Black ancestry.

Returning our attention to the ambiguous man of the hour, Alexander Twilight…

You’d think Alexander Twilight would be questioned about his appearance based on the flimsy yet pervasive one-drop rule. You’d think the state of Vermont would figure out he was Black just ten years ago. However, the 1810 Vermont census taker was comfortable judging Twilight based only on how he looked: like a “swarthy” white guy.

Why, in 1810, was the state of Vermont so chill about letting a Black guy become a white guy?

“Maybe we shouldn’t have had so many Black children” – American slaveowners

Race, in the sociological sense, is primarily determined by two factors: looks and relatives. There’s a big conversation to be had about cultural factors, but let’s talk systemically for now.

The racial identity of Alexander Twilight pokes a small but important hole in the structure used to keep Americans racialized. In 1810, Twilight’s appearance was enough to make him white. But if white Americans were historically paranoid about race, why wasn’t Twilight’s darker complexion the subject of more scrutiny?

Slavery.

As long as slavery enforced the inferiority of visibly Black people, the occasional Alexander Twilight-like case—often close descendants of slaveowners who raped enslaved Black women and freed their mixed children—did not matter. Even free Black folk lived at risk of being kidnapped back into slavery, often with the help of Northern state law enforcement. White Americans could sleep easy knowing there was no way Black people, broadly, could lay claim to their places in society.

It’s obvious, then, why the one-drop concept became so popular after abolition. It’s simply a reaction, a sloppy, panicked reaction, to the inclusion of visibly Black people in free society.

In 1895, South Carolina congressman George Tillman pleaded with state delegates to allow marriage between white people and people with “any” African heritage. By that broad definition of Blackness, Tillman said, no delegate on the floor was a “full-blooded Caucasian.”

White policymakers in the late 19th century knew “white” was a myth. And with Black people freed plus countless mixed descendants of slaveowners, the myth was on its deathbed after the Civil War before it was vigorously shaken back to life by Jim Crow laws.

This is why the definition of “one drop” differed from state to state: a fixed percentage of Black heritage in the very racially-mixed South would have immediately made thousands of respected white families Black. As long as the rule had wiggle room, white people in power could decide who was allowed into whiteness on a case-by-case basis.

So, to recap:

- Race in the U.S. was based on looks when there was a system to ensure those who looked Black stayed at the bottom. This is why Alexander Twilight went from Black to white so easily in the midst of chattel slavery.

- Race was based on heritage when visibly Black people entered society as free people. It is by this rule, hypodescent, we understand Twilight to be Black in hindsight.

- When white policymakers accepted whiteness was a lie, they committed to patching up the holes with Elmer glue sticks and notebook paper, constantly living on the edge of an existential crisis.

We already know race is made up. Your point?

In the past decade, we’ve become very good at recognizing social constructs. Everything in this piece thus far has been explained in much more detail by leading scholars such as Yaba Blay. But imagining solutions to them? Not so much. In fact, regarding race, popular discourse sees us reusing the same tools racist white policymakers used to stratify this nation.

Rather than showing more concern for light-skinned Black bodies being playgrounds for whiteness’ myth-making, many Black Americans have lost patience for the nuance of light-skinned and biracial Black identity. The worn patience is not without reason: noteworthy biracial and light-skinned Black folk often center themselves in talks about racism with a painful lack of self-awareness. These celebrity blunders being elevated into focal points of the discourse only derail it further.

We want light-skinned and biracial Black people to recognize the benefits of their proximity to whiteness. What we must resist, however, is envying them for it. To tell a light-skinned Black person they have no claim to Blackness because they’re not as exploited in the white world is to value the white world. Value the myth.

Alexander Twilight’s story helps us see that white supremacy stays alive by using groups of people as shields from the truth. In Twilight’s time, the shield was enslaved Blacks. During Jim Crow, it was second and third-generation European immigrants. Today, it’s the model minority myth placed on Asian Americans, the assimilation of many Latinx Americans, and light-skinned and biracial Black people.

The sooner these groups collectively recognize how whiteness exploits them, the sooner we can divest from the myths that keep racist systems alive. Regarding light-skinned and biracial Black folk, excluding them from Blackness only strengthens the historically false idea that Blackness can disappear into white America. If you’ve been keeping up, you know that it cannot.

If the endgame is destroying the racial caste system, the borders that protect whiteness must be torn apart. When we argue about which light-skinned Black people in the public eye are worthy of Blackness, we’re constructing the borders ourselves. We’re doing the work of racist white policymakers for them. Whiteness is an identity that requires division. Black liberation, which would lead to liberation for all, requires unity.

Liberation can’t wait for every individual to figure out who they are in the world. But while skinfolk ain’t kinfolk, kinfolk should aim to free all skinfolk. Anyone that has adjusted themselves—their literal selves—in order to pass through the white world needs to be included into Blackness. Stories like Alexander Twilight’s are Black stories, practical jokes on America’s ruling class that weaken the borders of whiteness.