How many times have you read this story?

Up-and-coming rapper with some momentum in his career violates his parole and gets sent back to jail.

More than enough rappers have been ridiculed in headlines for such events, usually without a second thought for how cruel and petty parole is meant to be. Meek Mill’s long history with Philadelphia’s criminal justice system, captured in the 2019 docuseries Free Meek, is just the tip of the iceberg when discussing the racist injustices of parole. But despite this story’s familiarity, FNF Chop’s version of it is unique.

FNF Chop is the first rapper of TikTok fame to get caught in the rapper-on-parole trap, with his 2019 song “Walk Down” getting a fresh wave of attention from a dance challenge based on the song. The two-month old music video is quickly approaching the million views mark and the single has shot past 2 million streams on Spotify, a good chunk of them coming in the past month.

As his music racks up plays, Chop approaches a year spent in Richmond Correctional Facility in Virginia where he’s caught COVID-19 twice since May 2020.

FNF Chop’s recent success with “Walk Down” and the state of the world during his time behind bars shows us the more things change, things stay the same. To paint this picture in paragraphs, I was given the chance to speak to Chop and his manager FNF Levy by Dark Matter Media, the PR firm representing Chop.

The following is a snapshot of an artist at the intersection of TikTok virality, a global pandemic, and a racist justice system.

FNF Chop, the artist

With a strong handle on the punchy DMV flow and a penchant for fun dance moves (his comical take on Hit Dem Folks is a personal favorite), it was only a matter of time before Richmond rapper FNF Chop got looks. “Walk Down” is doing the biggest numbers now thanks to TikTok, but videos for other infectious singles like “ABC’s” and “Drums and Drakes” confirm Chop’s appeal.

No FNF Chop video is complete without spontaneous group choreography and, so far, no Chop hit is complete without a Khroam beat.

Often relying on 808s or troublemaking piano arpeggios for melodies, Khroam has spent years making the rattling, stripped-down beats that define the DMV sound. Artists like NLE Choppa, YungManny and Xanman have walked Khroam beats before, and FNF Chop is poised to make this sonic wave bigger.

“For the most part it’s the drums, I love the drums. Toms, snares, I love drums … When I hear that shit it just makes me get up out my seat.”

At 22 years old, Chop is still new to the craft of rap. He’s only been rapping for about two years, a move inspired by the ennui of an earlier jail sentence.

“It wasn’t shit else to do,” according to Chop.

“He was callin’ me every single day and he was rappin’,” Chop’s manager FNF Levy fondly recalled.

Even on the outside, Chop’s story is defined by a desire to make it out. Noticing how rare it was for his peers to travel beyond their tristate stomping grounds, much of Chop’s drive is the will to not end up a statistic.

“[Being from Richmond] taught me to strategize and move a little different … A lot of people haven’t traveled or went to different states or places. Like spendin’ nights out in Miami, or Atlanta, or Baltimore.”

The willingness to leave his bubble is a factor in Chop’s impressive two-year sprint to start his career, a mindset he credits in part to his FNF—Family Never Folds—team. But while “Walk Down” continues to bubble and his latest project No Exit dropped on New Year’s Day, Chop’s legal troubles plague him like a nagging hamstring injury.

Even when you are done serving time in a U.S. jail or prison, the legal system is most likely not done with you.

A. Deonte Gaines, the young Black man being held back

After serving time for unlawfully possessing a firearm, A. Deonte Gaines, FNF Chop offstage, got out on parole like many Americans who have been to prison. But like a disproportionate amount of Black Americans, a parole violation—not a crime—is what landed him back in prison.

“I missed a meeting with a PO. Sometimes I’ll show up and they reschedule, or they’ll show up and I gotta reschedule.”

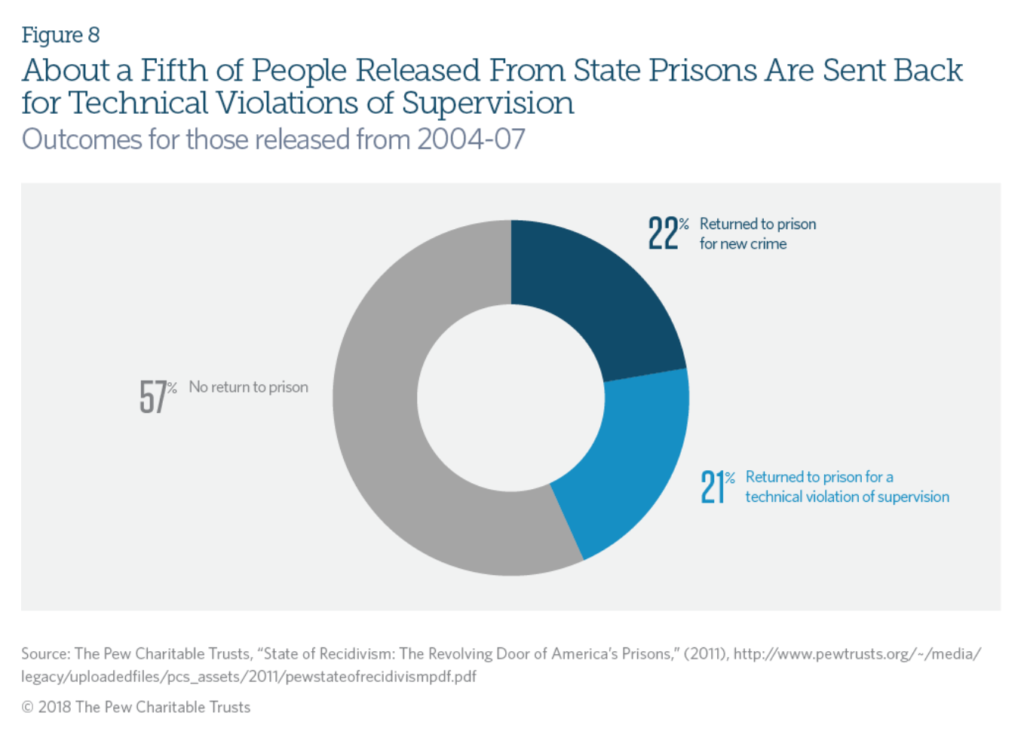

The frequency with which “missed a PO meeting” and other technicalities are used as reasons to lock someone up is frightening. In a three-year study, the Pew Charitable Trusts found that 21 percent of people released from prison are sent back for a violation of parole/probation. And whereas 1.23 percent (1 in 81) of white American adults are on parole or probation, the rate nearly quadruples to 4.3 percent (1 in 23) for Black American adults.

For a young Black man on a path to improve his life like FNF Chop, the sticky tentacles of the law are nearly impossible to shake once they get you.

FNF Chop is no stranger to this reality, and he has quickly learned how his newfound clout makes the target on his back bigger.

“Police know who I am so they target me more than the average person. They don’t want to see anyone rappin’ with a buzz make it. If they heard of you and you look like you gon’ make it out, they’ll be out to get you.”

Treatment in Prison

COVID-19 has left racism in America naked and exposed. More explicitly, it’s shown us that racism isn’t just in the systems waiting to be purged. Racism is the system. While it’s been most visible in the healthcare system, the carceral system has been even nastier.

As of April 2021, less than 10 percent of the American population has contracted COVID. But a whopping 20 percent of the U.S. prison population caught COVID-19 by December 2020. Four months later, it’s hard to think the rate hasn’t seriously increased.

It’s bad enough that FNF Chop is now in prison for something he can’t be charged for. Tack on two separate cases of COVID-19 in six months, and you’re left wondering if justice really exists in our justice system.

A rough patch in the call connection with Chop saw Levy step in to describe daily life in Richmond Correctional Facility. The descriptions captured routine dehumanization through neglect and social isolation.

Inmates in Richmond Correctional Facility are grouped by pairs limited to bunk beds held in a large open space. The lack of privacy is often solved by inmates with bed sheets draped over the top bar of a bunk bed. If correctional officers think inmates have been hidden from view for too long, they threaten to take away resources like electricity.

In fact, for a reason unclear to Chop and Levy, inmates were not allowed to use the phones when our interview was scheduled. Chop had to speak with me on a low-quality wifi call with a tablet, hence the occasional input from Levy.

Worse yet is the facility’s COVID-19 protocol. An inmate who tests positive for COVID-19 is sent to a pod with other infected inmates for a loosely enforced two-week quarantine. What else happens?

Nothing.

“It’s inhumane,” Levy tells me. “They don’t interact with anybody else, the COs don’t want anything to do with them. They’re like cattle.”

Chop first went down with COVID-19 late last August. It took him a month to recover from it. His second case was just this past February. As he comes up on a year in prison, the concern for Chop’s health and safety is as pressing as ever. The FNF team continues to haggle with Richmond Correctional Facility to get him out and back into music.

“They got a couple programs goin’ on. I got music. I just wanna do a couple shows and make some money.”

The programs referred to by Chop include the COVID-19 Conditional Medical Release and house arrest. Logistically, these processes are simple. But the facility has been in no rush to process these requests for the FNF team. Despite the poor health and oppositional treatment from prison staff, Chop has impressively remained in good spirits.

An FNF Future

All FNF cares about right now is “ensuring [FNF Chop’s] safety and making sure he’s being treated like a human being” says Levy. But the team has a firm vision of Chop’s future.

“Touring is definitely in the future. A lot of guest appearances on upcoming and familiar acts in the music industry.”

What Levy sees in Chop’s short-term future matches Chop’s self-confidence. Through it all, they both believe this is just the start for FNF. Chop has his eyes set on longevity.

“You gotta last long. You don’t want just two or three songs to pop. That’s not what I want at least. I gotta make this shot count.”

Citing Chop’s charisma, Levy thinks his artist will have another surge of popularity in the next couple of years, going so far as to say FNF will go global once Chop is home. While the rest is unwritten, it’s clear the long arm of the law hasn’t strangled FNF’s abundant hope and ambition. Chop’s Richmond supporters share in this hope, contributing with the #FreeFNFChop campaign and sustaining his buzz by shooting a second video for “Walk Down” with Chop joining in on a video stream.

As “Walk Down” goes strong, FNF Chop and his community are poised to keep pushing once he walks out.