Knowing that an ATC contributor felt strongly enough about my debut book to write a review of it means the world to me. I hope you find my self-published effort ‘Facing a Bottle of Henny‘ to be as hilarious and thought-provoking as Robby Vang has. But don’t listen to me, peep Robby’s take on it.

-Zander

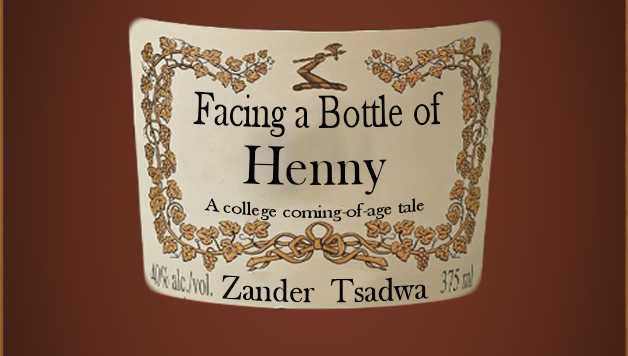

How symbolic can the physical appearance of a book get? Facing a Bottle of Henny punches me right in the face as I continue to stare at its mesmerizing appearance, wondering what’s in store for me. Its front and back covers are a dark caramel color, with labels of text that allow it to look just like a bottle of cognac. I’ve held bottles of Hennessy before, but what would people think if I showed up with this book in my hand? I’d tell them this…

Facing a Bottle of Henny is a coming-of-age story. It’s a memoir that rings true to many college students across the nation—more so minority students than others, but stay with me here. This narrative reveals stories and experiences of a single Black individual’s inclusion in a predominantly White private Catholic community. From stories of classism and awkward social events to noteworthy experiences with professors, Zander takes the reader through a journey that relives his college truth.

Taste test

The contents of this book are very similar to a shot out of a Hennessy bottle. Such sweet yet burning material in the form of valuable insights and truths the author critically consumed. I could tell you the main character runs into problems and he solves them with unique solutions, but the book was more than that. It was truly an adventure.

I also attended a private Catholic university; the main character was very relatable. Have I ever done or felt some of the things the narrator did? Hell yeah! Actually I’ve done or felt most, if not all, of the things the book exposed to me.

In the “Grad School” chapter, for instance, Zander highlights his journey during a summer research program. He contrasts the struggle of becoming a complete scholar versus a complete person. While describing his work to a staff member who told him to choose between spending years in grad school proving the value of his ideas or pursuing a passion project, I felt the dissonance in the relationship Zander was talking about a few paragraphs prior. The shot went down smoothly but the after-taste came back to pinch my throat.

Zander’s stories comparing good and bad experiences with professors really stuck with me. They reminded me of staff from my high school and university pushing forcefully to see me succeed in higher education, but often to feel better about their programs. However positive the work, it was more for their personal gain than mine. As a student of color, I had to learn the difference between well-intentioned and false-hearted educators.

Around the same time the narrator experienced these things in his college career, I was also dealing with questions about what made a professor helpful or harmful to their students. The most important lesson from “Grad School” was how you overcame that phase in college and the wisdom you gained from those interactions.

Feeling a buzz

One of my favorite chapters was “The African Apartments.” I could have replaced the word ‘African’ with ‘Asian’ and this chapter would have been a story of my own experience with local and international students of a shared background. As first-generation Americans, Zander and I both valued hanging out with these groups because it felt like home away from home. I smiled and nodded my head in agreement when I read, “the Apartments were a world away from the bland undergrad campus atmosphere.” While Zander was getting whupped in FIFA, I was getting whupped in Pro Evolution Soccer (PES). Ugandan guys rotated on the grill in his story while my Southeast Asian friends rotated on the hot pot dishes. In both cases, Heineken was the group beer of choice.

I think this segment was put strategically in the middle of the book. While you’re in the author’s shoes going through tougher times, “The African Apartments” is a light-hearted chapter that gives you hope. It was an experience that I felt came to the author at the right time of his life, enhancing his overall college experience, as did my parallel journey. Zander captures that unique experience well, one that, “helped me accept my cultural background at a time where it was difficult,” to use his very relatable words.

Other chapters such as “10 Deep” and “Ball Is Not Life” entertained me as well. I felt they were the falling action to this narrative’s resolution. “Deep” simply refers to the number of people in a group for anyone unfamiliar with the slang. In my Asian Apartment we were also 10 deep, collectively moving anywhere around the city, even if just for a meal. But the comfort of being able to go out and be the party at a predominantly White school was a feeling of empowerment, “making it [our presence] a strength rather than a liability,” in the author’s words.

In “Ball Is Not Life,” the comparison of basketball to writing in cursive was spot-on: something you rarely use as an adult, but if you were put on the spot, you’d better be able to show something. As someone who grew up in an urban community, I could appreciate a statement like, “you needed to learn basketball for the benefit of your self-esteem; the court was a coming-of-age test.” I admired this sentence so much I chuckled. Yet again, Zander’s stories reminded me of a group of friends I had.

While many of us bragged about basketball, the big competition for Hmong students was volleyball. Together with intramural students sharing the same gym space, teams became mixed and competition was at its strongest. Learning that, “ball was socialization [and] ball was education,” pushed our efforts to get together, build rapport and play uniquely like Zander’s friends in that chapter.

In a tracklist filled with serious shit, “10 Deep” and “Ball Is Not Life” were stories that made it easy to forget the book’s adversity. The chapters were well-placed tension releasers. They provided a feeling of acceptance after reading all the stories of conflict and exclusion. I’m sure many students of color have or want acceptance stories of a similar nature.

Just one more!

I can’t begin to fathom the impact this memoir will have on me. Most of the experiences in Facing a Bottle of Henny were very personal to me, and I applaud the author for capturing their essences.

I’d recommend this book to everyone. In particular, college-aged students living their own coming-of-age narratives might get a lot more value out of these stories. If you’re curious enough to question your own racial identity, or bold enough to face the psychological and emotional struggles of that journey, I hope this book will provide a cushion for your experience. If you want to just live in a young Black man’s mind while he goes through those things and laugh about it afterwards, pick up the book.

If you’re involved in your community, if you’re determined to follow your dreams and lead yourself into a great future, or even if you’re just lost and feel like you don’t belong somewhere, this book is for you. There are a number of parallels you can make between the experiences in this tale and your own.

These particular years of the author’s life were crafted and distilled into a symbolic bottle of Hennessy. He directly consumed it, as did I upon reading the book. Now it’s up to you to decide what you want to face. If you want some insight from just one specific narrative in a minority group’s collective story, I suggest you start with Facing a Bottle of Henny.

You can find paperback versions of FACING A BOTTLE OF HENNY on Amazon and CreateSpace. The Kindle ebook version is also available.

I love this peer review. Many people can relate or resemble this story in parallel to their own. The peer reviewer was able to capture and mirror the identity and narrative of the author into his own personal experience in respect to the Asian Apartments stories.

Thank you for the feedback, Tsua!