“Rapper,” a monolithic term

People feel threatened by hip-hop’s latest rising stars because we don’t have the language to explain how all these different artists are hip-hop artists.

A rock band can be anything from alternative to punk to pop rock. An artist who sings love songs over blues or jazz-tinged drum beats can be an R&B artist, funk artist, soul artist, or even a neo-soul artist among other things. But if you don’t quite sing, have end rhymes, and deliver them over an instrumental heavy on drums and bass, you’re just a rapper.

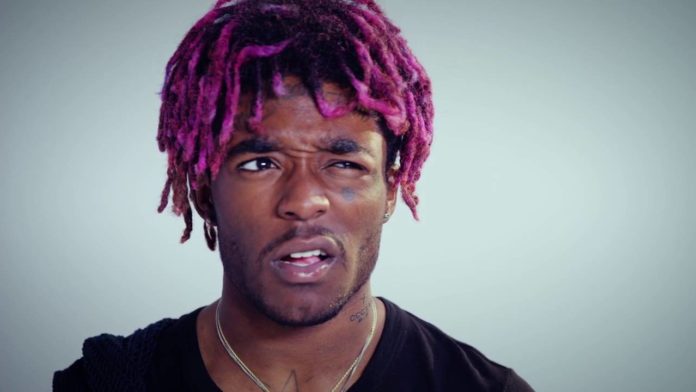

Future? Rapper. Lil Uzi Vert? Rapper. Kanye West? Rapper.

But none of the artists I just mentioned are similar enough to be considered the same kind of artist. The musical themes, image, and sound are different enough to command three separate categories.

Instead of trying to kick the Yachtys, Uzi Verts, and 21 Savages of hip-hop out of the community, maybe we can relieve the headache by placing them and similar artists in a category related to, but not completely within, hip-hop. This sentiment was shared by a surprisingly level-headed Cassidy, an artist passionate about bars, in a DJ Vlad interview in August 2016.

Putting labels on things can be complicated, but how else do you identify difference? Hate new hip-hop artists all you want, but their ties to the genre definitely exist. Your energy would be better spent understanding their place in it rather than dismissing them.

The challenge in finding new terms

Yoh over at DJBooth recently made the argument that Lil Uzi Vert can’t define himself as a “rock star” because the hip-hop platform is what has created him as an artist. Hip-hop fans, not rock fans, listen to Lil Uzi Vert. Hip-hop stations and blogs interview him, not NME or Rolling Stone. Therefore, Yoh concludes, he can’t duck the label of rapper.

Those points make sense initially, but this phenomenon isn’t as black and white as Yoh portrays. Sure, it is weak that he used his “rock star” label to avoid freestyling on a DJ Premier beat during a Hot 97 visit. But that situation isn’t a base stable enough for the point Yoh is trying to make. What concerns me about Yoh’s conclusion is its core belief: an artist’s platform (i.e. fans, media, external classification), not the artist’s brand, makes an artist what they are. I don’t buy it.

Despite insisting we call Uzi Vert a rapper, Yoh admits to Uzi’s stylistic difference, saying he, “may not make traditional rap music.” Since that’s the case, I’d like to see someone as knowledgable as Yoh try harder to find more appropriate language for an artist like Lil Uzi Vert instead of slapping an old, increasingly ambiguous term on him.

Arguing about classification is pointless if we don’t agree on what existing terms really mean. The core question is not, “What do we call new-age hip-hop artists?” The real question is, “What is a rapper?” We need to make sense of our existing language before we try to shove it onto our new reality. And we definitely can’t use new terms if we don’t truly understand our old ones.

How does the hip-hop community come to a consensus on what is and isn’t contained by the term “rap”? In terms of culture, the four original pillars of hip-hop have been seriously challenged. Graffiti is not essential to today’s hip-hop fans, breakdancing has been replaced by a revolving door of dance moves, and with so much technology at our disposal, the DJ/MC dynamic has been greatly altered.

Then what can we actually agree on?

It seems like the idea of the vocalist being the “master of ceremonies” and a producer being DJ-esque is still intact at its core. In the same way Rakim and Eric B, or Guru and DJ Premier, worked as a unit, many popular hip-hop acts still have right-hand men they call on to make their best work. Drake and 40, Future and Metro Boomin, and Young Thug and London On Da Track are all great examples. Though production and vocal performance in hip-hop is significantly different, the DJ/MC dynamic is still unique to hip-hop, both in recording and live performance. Even in the case of hip-hop artists who don’t have one go-to producer, it seems fair to consider artists who use this arrangement as hip-hop artists.

That being said, the term “rapper” is trickier. Whereas “hip-hop artist” captures the diversity, how do we identify “rappers” and “non-rappers”? When does the use of melody in a hip-hop song become “melody-driven” as Yoh described Lil Uzi Vert? When does vocal delivery go from rapping to singing? These are difficult questions, perhaps more appropriate for someone with a background in recording arts and music theory. But listeners, including me, do have an intuitive sense about these things.

Here’s my attempt at a rule of thumb, putting my intuition into words:

- A vocal performance with a primary focus on melody and voice manipulation via production technology is not a rap performance.

- Simpler terms: If people think a verse is hot mainly because of its sing-along appeal, and not for the lyrical content, it’s not a rap verse.

- Ex: Lil Uzi Vert’s verses on “Top” were not rap verses

- Simpler terms: If people think a verse is hot mainly because of its sing-along appeal, and not for the lyrical content, it’s not a rap verse.

- A vocal performance with a primary focus on lyrical technique (e.g. rhyme, narrative, metaphor, the shit you learned in English class) is a rap performance

- Simpler terms: If people think a verse is hot mainly because of how the words were put together, it’s a rap verse

- Ex: On “Broccoli,” D.R.A.M.’s verse was rapped

- Simpler terms: If people think a verse is hot mainly because of how the words were put together, it’s a rap verse

Let’s expand based on that. If an artist is considered quality mainly for their sing-along appeal, the term “rapper” isn’t the most accurate. Until a more accurate and respectful term is created (i.e. not “mumble rapper”), the term “hip-hop artist” should be able to encompass them.

Notice, I emphasize the word “mainly.” When you think about rap in the terms I laid out, it becomes difficult to apply to many of today’s hip-hop artists. Was Future mainly rapping, singing, or melodizing on “Codeine Crazy”? What do we call Lil Yachty’s verse on “Broccoli”? It has become obvious that great lyricists can make use of voice manipulation and melody, and that melody-driven hip-hop artists sometimes pay attention to their lyrical quality. Since all hip-hop artists employ some level of both melody and wordplay, we have to differentiate based on the balance of these two aspects.

Whereas Drake is today’s standard for the blurred line between rapping and singing, he still has very clear moments in his music when the musicality is coming from his rhyming ability, not his melody (e.g. “Weston Road Flows,” his switch-up on “Used To This”). Whereas Kendrick Lamar is traditional hip-hop’s golden child in today’s game, he has clear instances where his verses are driven by melody (i.e. his feature on The Weeknd’s “Sidewalks”).

Getting our heads around this issue is a lot of work. But hip-hop’s sound has grown into the mainstream much quicker than anyone could have anticipated. Instead of its constituents fighting over who’s version of hip-hop is “truer,” wouldn’t subgenres help everyone acknowledge the beginnings and evolutions of the genre?

Allowing for branches to grow instead of fighting to keep things at the roots makes for a more beautiful tree. Collectively, hip-hop needs to frame the relationship between old and new responsibly.

UPDATE (8/9/2019): HipHopMadness turned this piece into a video. Check it out here!