When I first listened to Ryan Beatty’s Calico just a few months ago, it felt like bumping into a kindred spirit and being wrapped in a long, warm hug that balmed the soul.

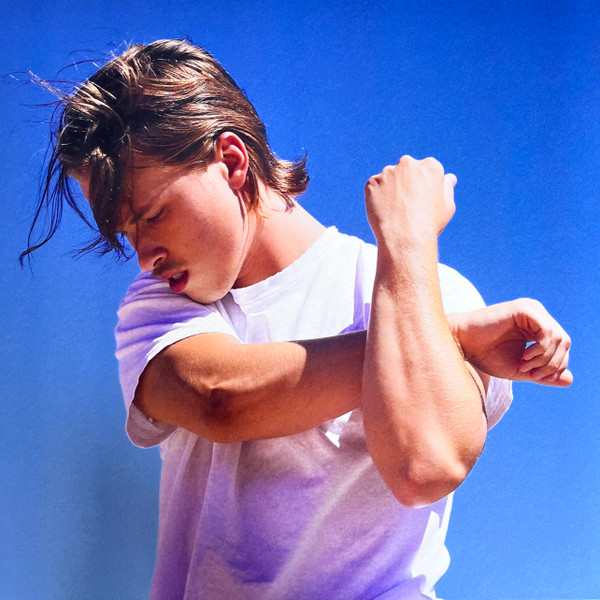

I was already a casual fan on the strength of his first two LPs (2016’s stellar Boy in Jeans and 2020’s even better Dreaming of David) and collaborations with Brockhampton, but Calico felt as if it came out of the blue — quite literally given the album cover and I had no idea it had been out for a few weeks — and punched me right in the guts when I needed it the most.

“Homosexuals have made a covenant against nature. Homosexual survival lay in artifice, in plumage, in lampshades, sonnets, musical comedy, couture, syntax, religious ceremony, opera, lacquer, irony…”

– Richard Rodriguez, “Late Victorians“

I rang in 2024 at a house party thrown by a gay couple, surrounded by a coterie of other gays. Troye Sivan’s Something to Give Each Other was blasting for most of the night (when was the last time gay guys fawned over an actual gay artist to that extent?). After midnight Spin The Bottle ensued, followed by the usual booze-and-sex-talk-laden debauchery. Then the obligatory viewing of a Drag Race franchise. The ultimate homosexual existence. It’s all supposed to make me feel the ultimate happiness too, right?

Well, not quite. But it was a much-needed celebratory release after the absolute hell of 2023. It was a year that I could only describe as deeply disorienting and soul-crushing: being abruptly dismissed from a beloved job, facing difficulty in landing another, and losing long-time companions, both animals and humans … the year felt simultaneously too long and too short.

Calico opens with its very thesis statement. Centered around a subdued piano accompaniment that gradually gives way to a strings section and electronic flourishes, “Ribbons” sums up the album in a single sentence: “It’s brave to be nothing to no one at all.”

The beauty of Calico, however, is less about its confessionals and more about its striking ability to render those confessionals often oblique and abstract, even non sequitur. In the age of sickeningly earnest introverted power ballads, this is a considerable feat.

Take for example “Cinnamon Bread.” Its subject matter — being emotionally invested in a sexually ambiguous man — easily hits close to home for many gay guys, but Beatty steers clear from potentially well-worn clichés and pivots to intriguing turns of phrase: he compares the contrast between his inner turmoil and stoic, accepting façade to Infinite Jest (after David Foster Wallace’s 1996 behemoth of a novel that explores, among others, the whims of addictions to drugs, sex, and fame) and the titular noun, before making allusions to giving his jock of a love interest head a few lines later.

“All the men you’ve loved / The women you’ve loved / They all got something to say… It couldn’t keep me away,” Beatty trails off, ever in that gorgeously hushed, intimate baritone, to a cacophony of folky guitar strums, soft bass lines, and laid-back drums. It’s this winning trick that informs the entirety of Calico: the words may read as incoherent, stream-of-consciousness mumblings of a troubled mind, but the music is all no-holds-barred sincerity. You could feel how Beatty had acquiesced — or was learning to acquiesce — to newly-realized inconvenient truths.

I was around Beatty’s age at the time Calico was in conception when I wrote two poems titled “Smoking Weed” and “Chemically Settled” and had them published. Both dealt with the uneasiness of the existential crisis I was grappling with between the ages of 25 and 26, a scientifically-proven rite of passage into adulthood.

“At the time, I was feeling a shift in myself. I was stepping into my age. [It was] really feeling like the beginning of my adulthood,” Beatty disclosed in his Apple Music interview with Zane Lowe. “It was scary. I had just put out [Dreaming of David] and I had this feeling that the next time I was going to put a record out was a long time from then.”

It’s also quite scary to notice the parallel between Beatty’s more understated (and I daresay masculine) appearance — no more of that Aphex Twink moniker — and mine circa 2018 and 2019, as I was losing weight and deliberately growing facial hair for the first time in my adult life. That mid-20s shift is empirically real, y’all.

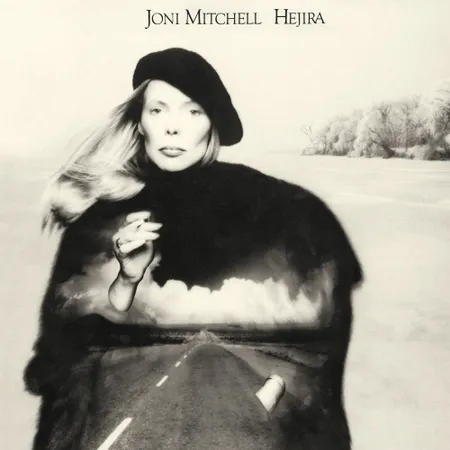

Around this time too, I had Joni Mitchell’s Blue on constant repeat, especially her signature song “River.” Whenever it arrived at that line — “I’m going to make a lot of money / Then I’m going to quit this crazy scene” — I would just be crushed, feeling so seen by how much truth it held for me then. It rings all the truer now. As per Beatty’s admission, however, it’s Mitchell’s other landmark album, 1976’s Hejira, that served as the primary influence for Calico.

This is most evidenced in “Hunter,” a sprawling, arpeggiated seven-minute opus which, all things considered, also proves to be the album’s centerpiece, replete with imageries of hunted deers, horses in the stable, frost-covered meadows, cedar trees, and Chevy trucks. It also ends with probably the album’s most striking admission: “I’ll be gone for a while / And I don’t wanna be found.” Being nothing to no one boils down to freedom and isolation in the same breath.

Both Hejira and Calico are rife with a sense of alienation and soul-searching qualities. But whereas Hejira is restless and meandering, Calico is resigned and soothing. Ultimately, it’s an album about coming back to oneself, a point that Beatty quite literally drives home often with repeated mentions of his family home and Californian upbringing.

Nowhere is this more candidly done than in the touching closer “Little Faith,” wherein Beatty recounts taking “a pill from the palm of an angel,” regretting not watering his dead plant enough and likening this to his perceived lack of effort at working on himself, and realizing how his mother always knew he was gay even before he did. Adulting means taking stock of where you’ve been and taking responsibility for where you’re going next, after all.

Calico is only nine tracks long but feels well-rounded and full-bodied — not one number is out of place or weighs down its overall flow thanks to Beatty’s sophisticated melodic turns and Ethan Gruska’s cinematic yet unobtrusive production.

Undoubtedly, traces of Gruska’s past production work — most notably on Phoebe Bridgers’ monumental Punisher — are all over Calico, especially in cuts like “Bruises Off The Peach” (easily the album’s most overtly pop moment, harking back to his earlier, R&B-tinged, Frank Ocean-indebted recordings) and “Andromeda,” which recalls the cosmic heights of Punisher’s “Halloween” and Weyes Blood’s 2019 track of the same name at once.

In a more just world, Calico would have turned Beatty into an across-the-board critical darling and significantly boosted his profile beyond the ghettoized “queer pop” tag. But perhaps there’s still little room in the discourse for more modest and introspective work by a gay/queer musician, even more so in a year that also produced club-oriented, maximalist pop in the vein of Something to Give Each Other and Sam Smith’s Gloria to name but a few.

Or perhaps, this has more to do with how gay culture still by and large glorifies urban escapism at all turns — clubs, bars, and other big city establishments — despite the crippling loneliness or gaping socio-economic discrepancy that it entails, especially if you’re anything but White and cisgender (and preferably masculine-identifying). Sometimes, even the decision to pulang kampung or a gay arranged marriage doesn’t seem all that shabby, as famously quipped by Beatty’s contemporaneous forebear Jay Brannan: “They say there’s no love left in the big cities, it’s kinda true / I guess you’ll find me coming soon to a small town near you!”

***

With the thrills of the New Year party slowly subsiding, I lay alone on my friends’ couch and everything that had just transpired was rewinding in my mind’s eye.

All the bravado and bitching, the kissing and flirting that amounted to nothing at all. All the animal-containing dishes I had no other choice but to munch on since it was a potluck and I was still in between jobs with next to no money, a growling stomach, and a sudden desire to blend in. All the city-inhabiting domestic and wild animals that were most probably harmed by the excessive amount of fireworks and firecrackers.

I thought about how I got into animal activism because modernity has failed us — and yet I am still very much complicit in its perils and pitfalls, still a city dweller too used to the urban existence to actively make efforts toward another way of living.

Then it began playing in my head: “It’s out of my hands / What can I tell you? / I’m not losing it / I’m just having a laugh…”

Beautiful perspective. I’ve been listening through the album since it’s release. There are still so many feelings that I get out of it. Great work!