In 2020, grimy Buffalo rap crew Griselda managed to bring the mainstream to them. Their January performance of “Dr. Bird’s” on Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show proved an authentic, technically superior delivery of asphalt raps can still grip the nation’s attention. But just 11 days before Westside Gunn, Conway the Machine, and Benny the Butcher hit the stage in New York, an Atlanta-by-way-of-the-Bronx rapper marked two years of extreme vocal pitch experimentation with the now-viral single “4 DA TRAP.”

Firstly, bless this home we call hip-hop, a mansion with forever changing dimensions that can house the grittiest traditionalists on one end and 645AR on the other. Despite my old frustration with how we categorize styles of hip-hop, the culture should be proud that the Freddie Gibbses and Roc Marcianos of the game can eat along with the Cartis and Keeds.

Secondly, the lengths 645AR has gone with his vocal meddling mark a much-needed checkpoint. Melody has always been a part of hip-hop, regardless of what snooty music professors and petulant “intellectuals” have said over the years. (Even our daily speech patterns have melody, you frauds.) But one major marker of the evolution of rappers from era to era is the frequency with which melody has been emphasized.

Melody: The Shy, Supportive Partner of Lyrics That Realized Its Worth and Started Showing Out

…rappers have since been playing in a chaotic game where sound matters more than similes

From hip-hop’s inception to the early 1980s, rappers were known for simple, lyrically light flows meant to ride the waves of funk and disco breaks. That is Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” and your “On the mic, (insert name) don’t play/I walk that talk every single day” type of rhymes. While melody was present here, it didn’t do much aside from help the MC tag along with the beat on mostly fun party records.

Lyricism increased in importance when rappers like Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, DMC of Run-DMC and LL Cool J turned up in the 80s with dense internal rhymes and stripped-down instrumentals which put rappers front and center on records. Though these artists made lyrically clever performances the new standard in rap, melody was the X factor, a subtly growing force that made flows more advanced by emphasizing certain syllables and changing the tone of select bars, usually within limited pitch.

As these more dexterous MCs started seeing commercial success, mainstream America wanted more Black American stories. Big acts of the late 80s and early 90s continued to win by elevating rap’s technical standard (e.g. A Tribe Called Quest, Wu Tang Clan, Gang Starr), but rap was now visible enough for rappers to focus more on aspects like social commentary (e.g. Ice T, NWA, Public Enemy), storytelling (Slick Rick), and showmanship (MC Hammer) without an obligation to push technique further.

Once hip-hop went mainstream, the rate of change and innovation became a whirlwind. The late 90s saw technical rap GOATs emerge like Biggie, Eminem, Big Pun, and Busta Rhymes that took Rakim’s principles to the max and sonically left boom-bap behind. This era also gave us artists who distinguished themselves with charismatic, uniquely melodic vocal styles like Snoop, Pac, and Lauryn Hill. And while the post-2000 evolution of the craft of rap does have major checkpoints—Ja Rule/50 Cent’s thug croons, Kanye’s 808s, Drake’s Take Care, Migos’ “Versace” and maybe Carti’s Die Lit now—rappers have since been playing in a chaotic game where sound matters more than similes.

A 2016 analysis done by Ethan Hein, a Doctoral Fellow in Music Education at New York University, demonstrates how essential melody has been in rap from the jump. Much of his writing over the past decade in academic music journals as well as his personal blog is on hip-hop, including this piece where he runs a capella verses through the software Melodyne to visualize melody in seemingly unmelodic verses.

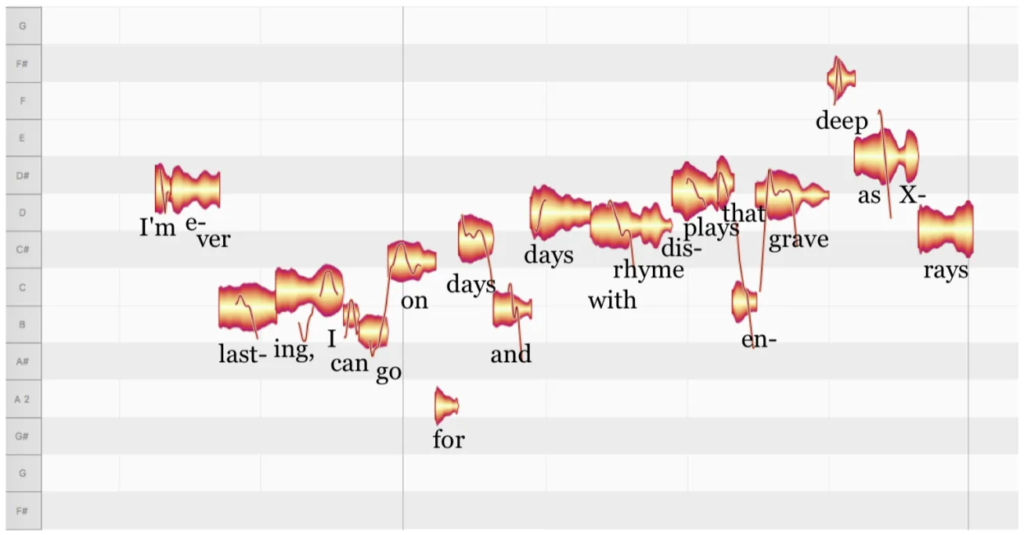

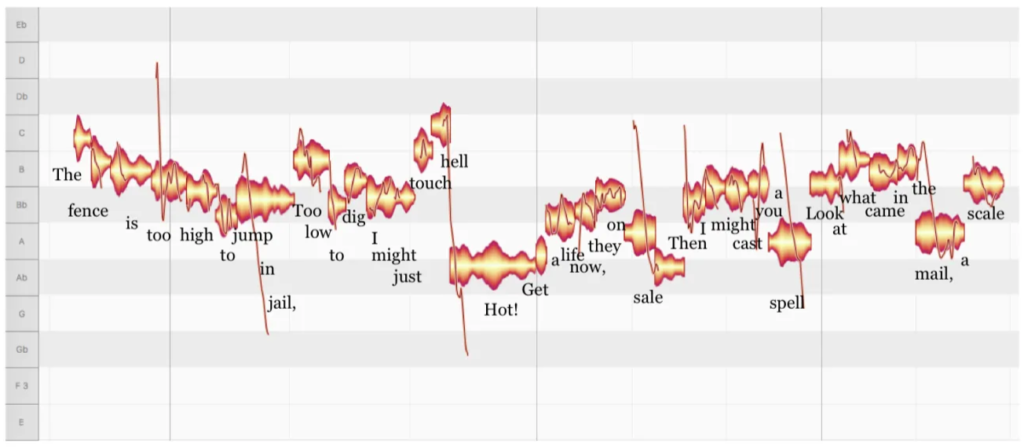

Here are graphs from Hein’s experiment of the melodic patterns in snippets of two different verses, Rakim’s first verse in “Follow The Leader” (1988) and Andre 3000’s first verse in Outkast’s “B.O.B.” (2000):

Melody and Lyrics: Who Wears The Pants Now?

If Rakim’s flow can hit that many notes in 5 seconds, imagine what a graph of Lil Uzi’s “XO Tour Llif3” or Young Thug’s “Wyclef Jean” would look like. Now consider 645 AR’s “4 DA TRAP,” rapped in a voice so high only the occasional word and note changes within the key of Squeak can be heard clearly, a rap verse as close to pure melody as possible.

Throughout the history of rap as a craft, melody has grown in importance as hip-hop culture has reached more casual fans. But in rap, the wordiest genre of music, Miss Melody has always served the aims of Lady Lyrics until very very recently. In the cases of post-Drake melody-driven stars like Uzi, Post Malone, and Playboi Carti, lyrics are used as the vehicle for vibes. Like any good pop or R&B songwriter would tell you, lyrics are only as valuable as the strength of the feeling they get across.

“Or do you not think so far ahead?” is not a particularly deep line in “Thinkin Bout You,” but Frank Ocean needed the word “ahead” to stretch that last falsetto note and make you feel suspended in time-warped heartbreak. 645AR says he takes his songwriting seriously, taking time to, “figure out…how I want it to compliment the melody and shit.” Even though catching any lyrics in “4 DA TRAP” is nearly impossible without rewinds, how 645AR chooses to flow makes the vocal performance an effective one.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In the last 10 years, rap has been overtaken by the #hashtag flow, the sing-rap approach, the triplet flow, the “ay” flow, expansion of ad-lib use, and now we have 645AR’s squeak flow, itself an evolution of the baby voice. While the story of the squeak flow’s impact is in progress, we can confidently say hip-hop has never seen this much genre-wide shift in the norms of rapping in this short of a timeframe.

Rap has always had weirdos and innovators like Kool Keith, ODB, and Lauryn Hill and Andre 3K singing and rapping before Drake. But the democratic free-for-all of online creativity has impacted rap more than any other form of music, to the point where one successful exception can become the rule faster than a Comethazine song.

645AR’s recent success deserves to be taken seriously. The deconstruction of rap thanks to agents such as Kanye West, Lil B, and SoundCloud has left hip-hop music in uncharted territory. But it would be a shame to not embrace all strange and successful artists that clearly bloomed from rap’s roots one way or another. Until a significant shift in subject matter requires a new collective rap dictionary, the rap game will continue to prioritize vibes over bars.

[…] This piece I wrote on the emergence of melody in rap technique also contains a pet study done by Ethan Hein, a Doctoral Fellow in music education at NYU, where he runs a capella verses of rappers such as Rakim and Andre 3000 through an audio software called Melodyne to track the notes and patterns in seemingly unmelodic rap performances. Here are a couple of the graphs Melodyne produced for Hein: […]

Thanks for the shoutout, this is a subject that is close to my heart. Several of the artists you’re talking about here are new to me, I’m looking forward to checking them out.

Very happy to have you read and reply, Ethan!

It’s awesome to see someone with your background in music take rap innovation seriously. It means a lot to me and will go a long way in defending the music and the culture it’s born of.

Playboi Carti and 645AR will blow your mind. Have fun.