Originally featured on Joe Molohon’s site, VG-Narrative

Videogames are rarely discussed in mainstream media. When they are, it’s usually in one of two ways: as a mind-blowing technological achievement (i.e. Pokémon Go, Oculus VR), or as a prime scapegoat for a disturbing new behavior trend among children and young adults. But what if you were told videogames could actually develop empathy rather than destroy it?

In comes Joe Molohon, a student at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, to debunk popular myths about videogames inciting violence. Let Joe walk you through the eye-opening research and experiences supporting the notion that videogames can actually teach us empathy.

-Zander

There’s an age-old argument out there that videogames are the cause of much violent behavior. It likely found its strongest case when critics connected the atrocity committed by the Columbine shooters to their extensive play of the FPS Doom, saying that the graphic violence of the videogame shooter likely inspired their later, real-world violence.

An article published by the New York Times in 2007, “Tying Columbine to Video Games”, cited research by psychiatrist Jerald Block that concluded that “Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold went on their shooting rampage at Columbine High School after their parents took away their videogame privileges.” But this is an old sentiment, one that echoes similar beliefs about movies, from around the 1930s and 40s. And in the case of Columbine, their violence is more accurately to have been a result of the mental conditions these two kids wrestled with (psychopathy and suicidal depression, respectively). It’s ridiculous to think that two 17-year-olds would resort to such extreme violence after something so small as losing videogame privileges. In fact, there is no proof to suggest the validity of Block’s conclusions.

If we support the idea that videogames can cause violent behavior, then it follows that we should believe all narrative forms to be able to inspire the same thing, including books and movies. I might argue that the graphic descriptions of A Clockwork Orange are several times worse than the fake, pixelated violence of Doom, or that a movie like Reservoir Dogs is much more likely to inspire violence with Quentin Tarantino’s aestheticized portrayal of it. It’s hypocritical to think that videogames alone should have this influence, when such ideas have plagued each medium throughout their respective lifetimes (book burnings or the FCC anyone?).

It’s difficult to gauge the negative effect what we see and play might have on us. There are so many factors that, unless you are the person committing the act, it’s unlikely you’ll ever truly know. It’s ridiculous to think that any one medium, as a whole, could be responsible for our violent tendencies.

In fact, I’d like to argue for the opposite. It is my belief that videogames, as an experiential medium, can teach us to be more empathetic, and to help us see things from another perspective.

Proponents of Mr. Block’s opinion typically refer to videogames as a unit when citing their violent nature. It isn’t videogames of a certain class, genre, or even specific videogame titles. It is videogames, in general, that are deemed to incite violence. And while most of the titles in the minds of these people might be first-person shooters like Doom, it just isn’t the case that these kinds of titles are relevant anymore.

Videogames have since expanded far beyond the violent stereotype, and certain titles have found great success without the inclusion of any violence whatsoever.

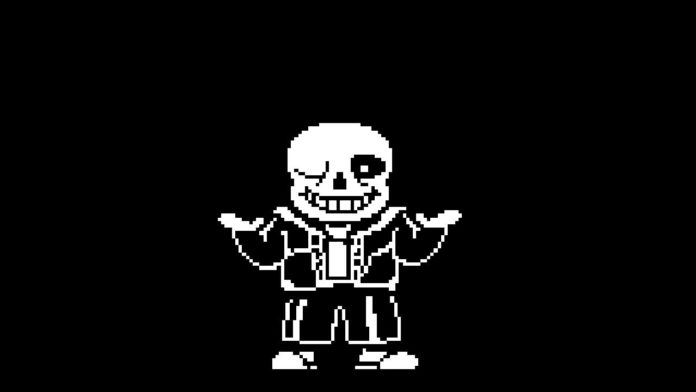

A great example of this would be the videogame Undertale.

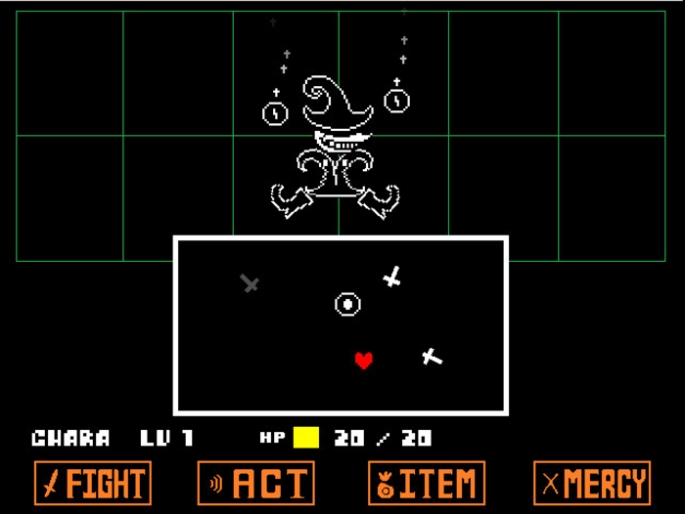

Undertale is a game that allows for a unique approach to violence. It doesn’t remove it entirely, but it allows for a player to progress throughout the game without any violence whatsoever—the “pacifist” playthrough, as it is known. Instead of trying to kill their opponent, pacifist players dodge the attacks of the monsters trying to harm them, spending their turns trying to convince them to stop fighting.

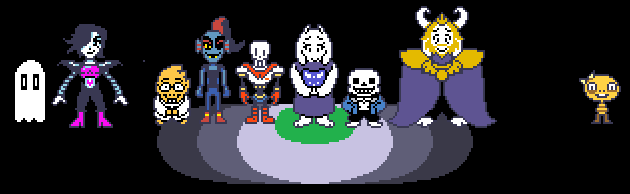

The pacifist playthrough is part of what garnered Undertale so much attention in the first place, there isn’t much like it elsewhere. And as one of three playthroughs, the pacifist playthrough is typically understood to be the “right” playthrough since this playthrough gives the player the most complete picture of the game’s story. In addition, it has a number of endearing qualities that make it popular. Dodging attacks and finding out each monster’s weakness is largely understood to be more enjoyable and requiring of more skill. However, most prominently, the bonus of the pacifist playthrough is getting to know all of the game’s central characters and the quirky monsters who live alongside them.

As a matter of fact, after completing the pacifist playthrough, there are reports of gamers being unable to complete subsequent “genocide runs”; their love for the characters of their previous playthrough was simply too great for them to kill them. I myself experienced similar feelings, and had trouble even watching a favorite YouTuber of mine go on his own genocide run.

It would be wrong to assume that this kind of emotional connection didn’t exist until Undertale. Rather, this kind of thing is something we simply haven’t had the opportunity to experience before in videogames.

In his chapter on empathy in his book How to Do Things with Videogames, Ian Bogost talks about the videogame release of E.T. (Atari). For of those of you unfamiliar with the game, it has a reputation for being infamously bad. Its sales and its concept were a total flop, with Atari being forced to dump hundreds of thousands of cartridges into landfills (Bogost 20).

The general consensus of E.T. is that it was simply a bad videogame. It’s a spin-off of a movie (never a good sign when it comes to games), has awful controls, and presents the player with a strong sense of confusion as to what the hell is even going on ever. So it’s interesting that Bogost should have a different take on its flop, largely citing the videogame’s decision to take power away from its players.

“No matter their frequency, complaints about E.T. assume that games must fulfill roles of power, that they must put us in shoes bigger than our own, and that we must be satisfied with those roles,” (Bogost 20).

At that time, it may very well be that gamers simply weren’t ready for a game that sought to take us away from the violent power-fantasies that were so popular (contemporaries like Galaga, Castle Wolfenstein, Dig Dug). But it may also be that E.T. simply didn’t have the hardware to create the experience it aspired to be.

From my own perspective, I see a game with an interesting concept that is poorly executed. While Bogost has a good point, it isn’t likely that all of its problems were intentional. After all, when the majority of your gamers don’t understand how to play your game, there’s probably something fundamentally wrong with the system. But Bogost does make a good argument for the appreciation of what E.T. tries to do.

“In the game, the player cannot easily predict the topology of the virtual landscape, and he or she often falls into wells. Once at the bottom of a well, the player can use E.T.’s ability to levitate to rise up and continue. While this feature of the game is universally panned for causing intense frustration, it also brilliantly juxtaposes E.T.’s purported powers with his actual weakness. Levitation, an ability that another game might deploy for advantage in combat, becomes a small victory that merely allows E.T. (and the player) to realize the possibility to be hunted,” (20-21).

From Bogost’s perspective, E.T. failed largely because it was a game that put players in a position of empathizing with the weak at a time when players were more prominently concerned with the cool things videogames could allow them to do. Things like destroy large armadas of alien space ships, jump twenty feet in the air, or whimsically dig tunnels through a cartoon underground. And while I agree, I would build upon this with the idea that E.T. simply wasn’t well-made. Even playing it now, at a time when we might be expected to understand and finally accept it, E.T. just doesn’t compare to its better-liked contemporaries. And it’s nowhere even close to a game like Undertale.

Bogost cites the empathetic quality of videogames as the ability to, “put us in someone else’s shoes,” (18). I think this is part of what Undertale relies on, but it isn’t everything. There are a few major problems and differences that we find when we compare the two games, side-by-side.

First of all, it’s important to note the failure that E.T. represents, compared with the huge hit that Undertale represents. Regardless of arguments about the environment E.T. was born in, it can’t be denied that the videogame was a flawed concept. A successful concept would have succeeded, like Undertale. This is important to note when covering differences between the two, as it is likely that these had something to do with the different trajectories of the games’ careers:

- Whereas E.T. puts us in the shoes of its central character, Undertale has us take control of a voiceless avatar that we name and fill out the personality for ourselves. Compared with what Bogost says about empathy, this kind of approach is contrary to creating understanding. But why, then, does Undertale succeed so well? E.T. presents us with a voiceless character, devoid of personality, whom it is frustrating to play as. There is little that is redeemable about the experience. Undertale, however, finds its empathy through the world around it. It isn’t the experience of playing as the “faceless” avatar that’s important; it’s getting to know all the colorful personalities of the world they exist in. The major flaw of the concept of empathy in E.T. (and of Bogost’s perspective) lies in assuming that empathy requires us to step into another’s shoes, and that we cannot simply learn to care about another’s thoughts, emotions, and being simply by being encouraged to get to know them. It’s important to note that the first-person avatars of videogames aren’t typically the characters most well-liked in series, unless they are given characterization outside of the player experience. (Does anybody really empathize with Mario after all? Isn’t it the quirky Luigi that everybody typically loves more?)

- Another problem we might bring up is that E.T. assumes the experience of empathy is what’s most important to the game. According to Bogost’s interpretation, E.T. is driven primarily by a desire to put a player in a position of weakness in order to create empathy. This means frustrating controls, sub-par graphics and a confusing and unfair system, all for the sake of making us care for E.T. by seeing how weak he is. This is a flawed assumption on a few levels. For one, it assumes that empathy only exists for the weak. True empathy is open to all, and the truly empathetic will be able to understand the position of all persons, regardless of their social status or whatever else, regardless of whether they’re human, animal, or alien. E.T. should not require its players to be weak in order to feel empathy for its characters. It’s important that Undertale does not rely on this. In the pacifist run, I don’t empathize with Sans or Papyrus because I see how weak they are. If I am playing a true pacifist run, I never kill or even truly beat these characters. Rather, I dodged their attacks until I could convince them not to kill me. Well, you shouldn’t fight Sans in a pacifist run, but that’s important to note too! Why does everybody love Sans? Because he’s funny and he’s kind and he’s got great personality. It doesn’t directly matter that he’s one of the most powerful characters in the game. True empathy comes from knowledge of another, not from weakness.

In comparing these two games and critiquing the words of Ian Bogost, I think we’ve come to a better understanding of how empathy can, in fact, be taught in videogames. There are a few important qualities that I think have to exist for empathy to be created between a player and a fictional videogame character, and they’re rather similar to what we might expect of a movie or book:

- There needs to be something there for us to connect with. The character needs to be fully fleshed out as an individual.

- We need to experience something with this character. It isn’t the first-person perspective that’s important, it’s really just getting to know these characters and see how they act in situations we might be able to connect with, as we experience them at the same time.

- The videogame needs to be engaging. This is the most important of the three, I think. Part of why E.T. fails, I think, is that it’s such an unpleasant experience to play through. It isn’t likely that any player would be open to establishing a personal connection with a game’s characters if he or she does not first enjoy the experience of the game. If I’m grumbling about controls or what I can and can’t see throughout, I’m not likely to care about the friendly banter it tries to distract me with in the cutscenes.

I think if you have these three things, then a videogame can engender empathy. Undertale is known for creating an extremely loyal and dedicated fan base, in large part because of the characters it created that everyone came to know and love. In playing Undertale, they established a bond with these characters, a bond that, in some cases, even prevented players from killing these characters in later playthroughs. Undertale presents peace as an actual alternative to violence, even as the significantly better alternative to violence, and it is one of the first games to do it well. Anyone who thinks that videogames only create violence should play this game before jumping to any major conclusions. The feels might be enough to convince them otherwise.

In the meantime, thanks for reading!

Best,

Joe Molohon