Originally featured on Joe’s site, VG-Narrative

These days, anyone with a laptop and wifi can record a quality song, publish a book, or take professional photos. But is all creative production free and simple these days? Specifically, can videogames be produced free of charge with the same quality and simplicity content like songs and photos are made by amateurs online?

Back with another piece, here’s Joe Molohon describing his experience making videogames.

-Zander

Anyone can buy and play a game. But can anyone make a game?

As videogames become more and more prevalent in our society, so too does game-making software. Major examples like GameMaker Studio and Unity are readily available to anybody with the cash and/or computer to run them. As a matter of fact, there’s a version of GameMaker that’s entirely free, and all it requires at most is the ability to run a simple sprite-based game like 1979’s Asteroids.

And this was something I did recently. Well, sort of. Using the free version of the GameMaker software (through my also-free Steam account), I created my own clone of Asteroids. It’s the imaginatively-named ‘Roids, and it’s about the fever dreams of a muscleman who must resist the temptation of an easy out that steroids represent.

I enjoy playing it almost as much as I liked making it, but it certainly isn’t a masterpiece. And that’s OK. But even this simple experience of creating a game across a period of maybe two weeks got me to thinking about the whole process. And it reminded me of a question that I’ve thought about for a very long time: can anyone truly make a game?

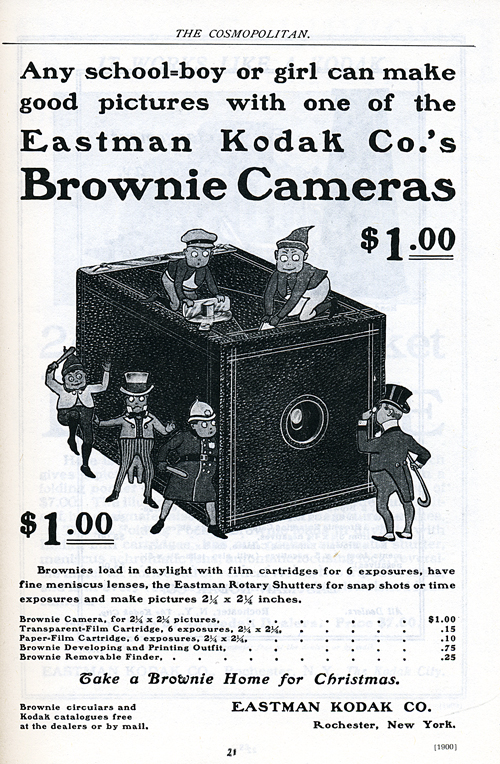

As Ian Bogost reminds us in How To Do Things With Videogames, there are many creative processes that have been simplified to the level of being open and accessible to the masses. With blogs (and blog-creating sites like this one) and online/independent printing presses, it’s fairly easy to be a writer. And with the relatively low cost of canvas and paints, you could follow a Bob Ross tutorial and be a painter. But the example that Bogost primarily uses is photography, and more specifically the example of the Brownie; the first snapshot camera ever developed, in 1900.

“It was about as simple as cameras get: a cardboard box with a fixed-focus lens and a film spool at the back. … The simplicity of Brownie cameras made them reliable, and their low cost (around $25 in today’s dollars when introduced in 1900) made them a low-risk purchase for families or even children. Millions were sold through the 1960s. Both camera and film were cheap enough to make photography viable. Easy development without a darkroom made prints possible for everyone.” (70)

As Bogost explains, the Brownie first introduced that understanding of photography that we are most familiar with today. For the majority of us, photography is a simple art, meant to be used in nature outings and at yearly family gatherings. Taking a picture nowadays is as simple as the press of a button, the accessibility of cameras is only increasing. Most of us even have a fairly decent camera built right into our phones, enabling a device we use primarily for vocal social communication to be used for visual purposes as well.

What the Brownie did for photography is the epitome of what technology seeks to do for all art forms; a simplification of the process to an extent that it can be done. It doesn’t mean that anyone can take a great photograph, but it seeks to enable the potential for anyone to do so, and at the same time making the act of taking and producing photographs much less time-consuming. It’s rather safe to argue that, since its genesis, the Brownie has taken photography in a direction that has strengthened focus on the art of photography, allowing photographers to spend more time on the formal elements of their shots, as opposed to wasting time on the tedious act of development. What technology achieved with the Brownie was groundbreaking, and we’re seeing similar effects in industries like book publishing and music production.

But is there an equivalent in the videogame industry? Could games be made with the push of a button?

Ian Bogost tells us that “there’s no videogame equivalent to the camera.”

“Game creation can never become a fully automated affair. Taking a photograph is easy partly because so much of the process goes on without us. … Film development can be outsourced to Wal-Mart, and digital images are ready for immediate printing or posting. Video is similar; editing, titles, and sound are all optional but easily added with tools that come with every modern computer. Writing isn’t as automated as image-making, but it’s a skill everyone uses in daily life. … Conversely, videogame creation exercises few common skills.” (72)

It’s true. Even with free software like GameMaker Studio, you won’t have a complete game simply by clicking the ‘run’ button. Even simple games like my ‘Roids require some fairly exclusive knowledge in their creation, including basic familiarity with CSS/HTML code and the ability to draw and map-out sprites and rooms. More complex games require more skills. If you’re going to create something like Mass Effect, you need to know things like animation, 3D modeling and sound design, things people go to school for years to learn. There’s a reason triple-A titles like Mass Effect take teams of hundreds of people to develop over long periods of time.

But even with this knowledge, I might argue that the democratization of videogames is plausibly coming.

Ian Bogost wrote his book way back in 2011. OK, so it hasn’t been a lot of time, but much has changed in the industry since then, and a few years in the digital world can equate to lightyears of progress. At the time of Bogost’s writing after all, people still remembered things like Microsoft Popfly. (Honestly, I’m still not sure what it was.)

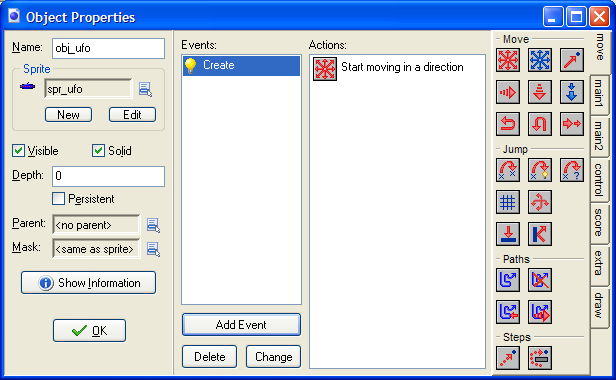

And if you were messing around with GameMaker back when it looked like this…

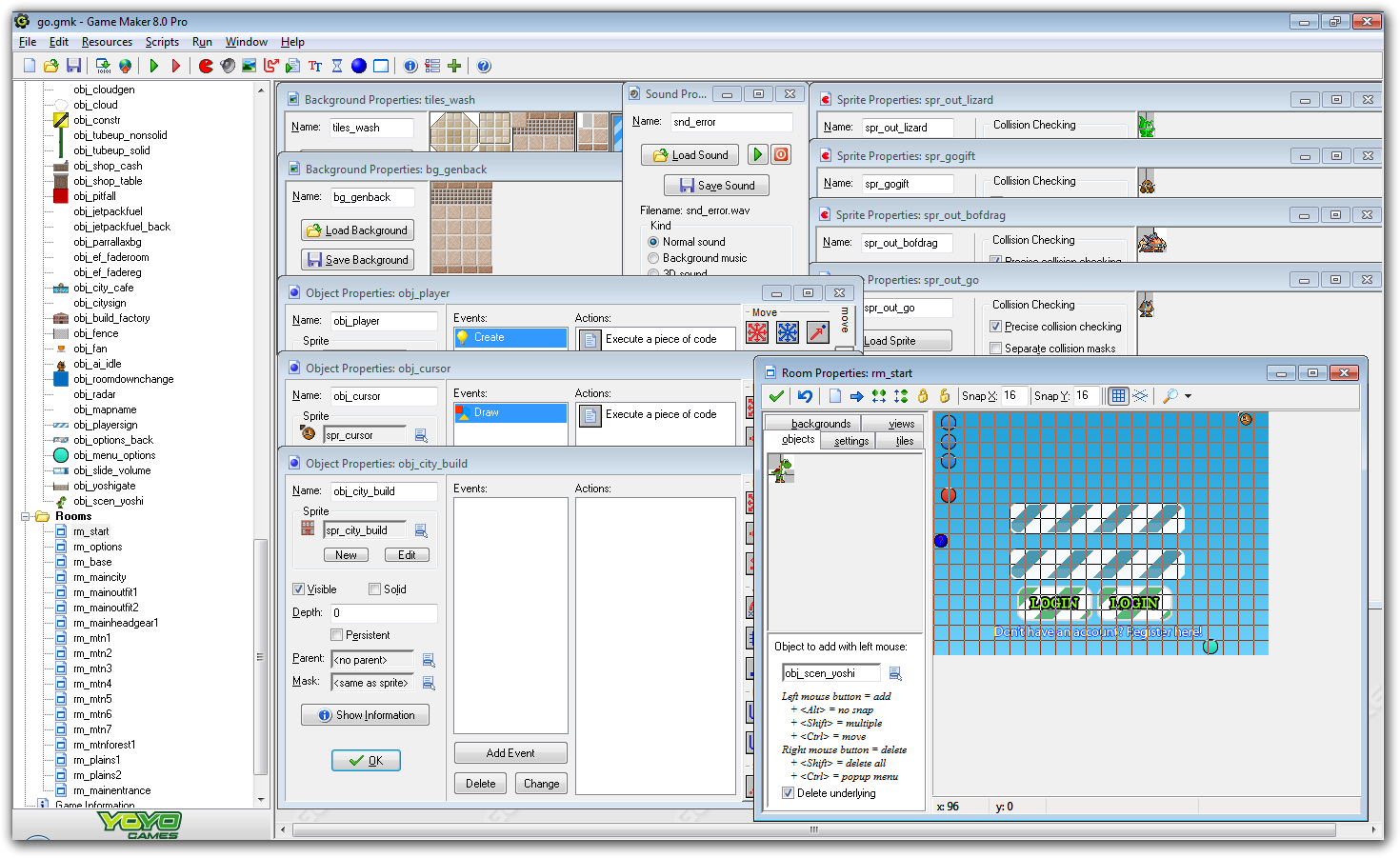

… then you’d probably be surprised to play around with it like this…

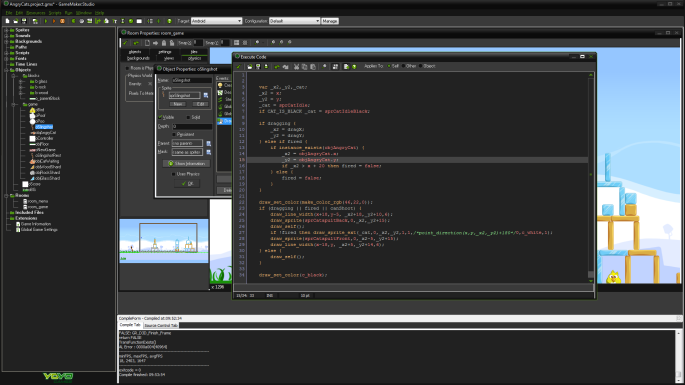

… and end up using it to make something like this.

It’s true that you need to know some stuff before you can make a game. But there are easy ways to obtain that knowledge. In making ‘Roids, I myself relied heavily on YouTube tutorials, in particular a series made by one Shaun Spalding (bless you, sir). Even if you need to know some stuff to get things to work, the miracle of the Internet might allow you to find that knowledge rather easily.

And there are other means to game creation than following YouTube tutorials. You see, I messed around with GameMaker back in its old and ugly days too, when I was a teenager. Back then, there wasn’t much in the way of online tutorials that I knew of. So what I did instead was mess around with the code of pre-existing games.

This older version of GameMaker used to include the entirety of some old-school arcade titles, like 1945, for example. While the software certainly allowed you to play these titles, it also allowed you to play with the code of these titles. Learning from and tweaking the code of games like 1945, I was able to make some simple games with my brother and my friends. They were primarily a reenvisioning of the concept, but I think we included enough differences—adding new enemies, new weapons, and multiplayer capabilities—that made the game our own. At some point, Santa’s War on Hell just wasn’t 1945 anymore.

(Wish I had a picture of that.)

It’s true that game creation isn’t necessarily as easy as taking a picture. But if you really want to make a game, I think you can find the resources to make that happen.

Thanks for reading!

Best regards,

Joe Molohon