The resurfacing of a century-old suspicion that legendary composer Ludwig van Beethoven had immediate African ancestry was one of Twitter’s 2020 highlights. Is the theory rooted in any genealogy or big context clues beyond his physical description? No. But it cracked our collective thinking about historical white-passing and how race has largely determined which great individual legacies are preserved.

In the debate about Beethoven’s race, the story of biracial Black violinist and composer George Bridgetower was unearthed. In imagining a Black Beethoven, we uncovered one. And here we are just a year later, with another titan of human achievement receiving the same speculation: George Herman “Babe” Ruth.

While we marvel at the possibility of a Black Babe Ruth, the truth, like that of Bridgetower’s, sits tormented in the shadows. Black Babe Ruth existed, and some went as far to call Babe Ruth the White version of him. But first, perspective on Babe Ruth’s impact.

* * *

The Perfect White American Sports Star

The Sultan of Swat, the Colossus of Clout, the Great Bambino and every other nickname the ragtag crew of kids in The Sandlot memorized. That Babe Ruth. The one who called his shot and lived off beer and hotdogs, among other mythical feats. Almost 90 years since his final game, Ruth is still arguably the greatest player the sport has ever seen.

One of three players ever to hit 700 home runs, the 10th highest career batting average ever, and he was a pitcher. A dominant one. He only pitched during his first five seasons which were spent with the Red Sox, but Ruth had a 94-29 record on the mound with an exceptional 2.29 ERA. Ruth regularly bested Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson head-to-head, and he even pitched a shutout in the World Series.

Ruth’s accomplishments do not sound real. He singlehandedly reshaped a team sport in a way that arguably no other American athlete has. And he could have very well been a Black man doing it, with speculation of his racial identity quietly pestering him throughout his career.

Scholar Antoine Hardy’s lighthearted Twitter thread is what opened this Pandora’s box. The thread assembled the best contextual information on the question of Ruth’s race during his lifetime.

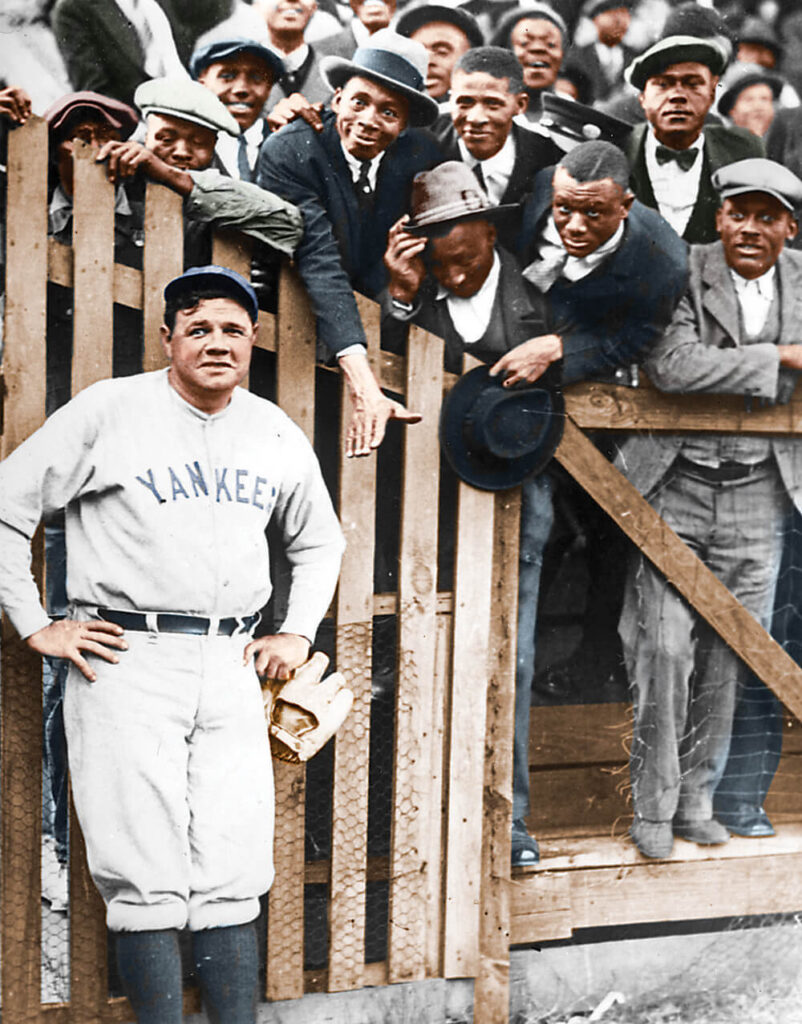

Not only did he have darker skin and stereotypical Black features, Ruth fostered close relationships within New York City’s Black community. Among other acts, he regularly barnstormed (i.e. did exhibition games) with Negro League teams, befriended famed entertainer Mr. Bojangles, and gifted Harlem crime boss Bumpy Johnson a watch. According to Ruth’s daughter, league officials kept Ruth from becoming a manager out of fear he’d break the “gentlemen’s agreement”—the de facto ban of Black players.

The possibility of great Western men being Black is compelling because it forces us to acknowledge racism in our view of history. Questioning Beethoven’s race came with scrutiny of the label “genius” and the role of social class in creating such geniuses. Questioning Babe Ruth’s race is focusing our attention on how America props up its white heroes and stifles its Black ones.

Josh Gibson Never Had A Chance

In the latest episode of The Right Time with Bomani Jones, Bomani Jones speculated with Shannon Penn about the Bambino’s place in history today if he was publicly known as a Black man in the 1920s.

“Here’s how we would talk about Babe Ruth: ‘Man y’all don’t even know. There was a Black dude that was the best player in baseball. And then one day, not only was he not playin’ no more, they took all his stuff out the record books!'”

Penn laughed at the idea and exclaimed, “He would have really been a legend then!” But the most poignant part about this informal thought experiment is that we don’t need to imagine it. Reality has done this experiment for us, and the conclusion is ugly.

You want to know what would have happened in the early 1900s if America’s greatest baseball player was Black? Enter, Josh Gibson.

Josh Gibson was a catcher who played in the Negro Leagues, with stints in the Dominican Republic and Mexico. In 16 Negro League seasons Gibson played 669 games—Negro League seasons were much shorter—roughly a quarter of the games Babe Ruth played in his career (2,503). In one-fourth of the games, Gibson hit 168 home runs, about one-fourth of the home runs Ruth hit (714). His career batting average is estimated to be .362, which would be the second-highest in MLB history and is 20 points better than Ruth’s. Other metrics like on-base percentage (OBP), slugging percentage (SLG) and walks are nearly identical between the two.

Gibson averaged a home run every 14.4 at-bats in Negro League play. That rate would be the eighth-highest in MLB history. Gibson would also have the second-highest career SLG, sixth-highest career OBP, and the highest single-season slugging percentage in MLB history. The only thing Josh Gibson didn’t do that Ruth did was pitch.

No legend is complete without their mythical feats. Much like Ruth, stories of Josh Gibson doing the impossible are endless. Of course there’s the claim of his 800 career home runs, including 84 in a single season. The worship of his short, compact swing, unusual in a time when power hitters swung out of their shoes. Then there are the tales of his strength, both true and exaggerated, including a story about a ball that fell out of the sky in Washington a day after he hit a monstrous homer in Pittsburgh. A Washington outfielder caught the strange ball and the umpire yelled at Gibson, “You’re out! In Pittsburgh, yesterday!”

Statistics to support the heroic profiles of Gibson and fellow Negro League stars such as Satchel Paige and Cool Papa Bell are hard to verify. However, the common belief that Negro League record-keeping was haphazard is inaccurate. The root cause of the Negro Leagues’ shaky professionalism is the same root cause for their very existence: racism.

* * *

It was the Negro Leagues, plural, because teams were independently owned and formed leagues across the country. Teams either disbanded or formed leagues depending on where the money was. Teams rarely had ownership of a home ballpark or a contract granting exclusive use of a field. Wages were unstable, so teams sometimes turned down league games to play higher-paying exhibitions. The lack of capital and stability made it difficult to schedule a season, a big reason why Rube Foster, founder of the first Negro League (Negro National League), made seasons so short.

With Negro League franchises often changing leagues, having limited access to fields, and having their best players playing many of their games in Latin America—echoed by WNBA stars who play in Europe during the “offseason”—it was virtually impossible for the Negro Leagues to have the infrastructure needed to preserve stats. If leagues struggled to pay their players consistently, how could they afford crucial staff such as full-time groundskeepers and bookkeepers?

Despite the steep uphill battle Negro League executives fought, the feats of stars such as Josh Gibson were recorded well enough for historians today to piece together a picture. Gibson didn’t get a career’s worth of action against MLB teams, but he hit .400 in exhibition games against them. In basketball terms, as Bleacher Report readers like to ask, this would be Steph Curry making 50 percent of his 3s in a season. Otherworldly.

MLB players didn’t take those games as seriously as Negro Leaguers who looked to prove themselves, so even that wildly impressive feat is dented by racist exclusion. And though the best Negro League and Dominican teams had talent as stellar as the MLB’s—until the MLB started poaching them in the mid-1900s—quality from team to team was inconsistent. The lack of validation from the Major Leagues during Josh Gibson’s career made it impossible for him to be known in the mainstream as the greatest player in baseball.

“What If Beethoven Was Black?” “What If Babe Ruth Was Black?”

George Bridgetower, the Afro-Caribbean violinist and composer who astounded Beethoven as a teenager, died poor in a nursing home crippled by arthritis. One “off-color remark” about a woman Beethoven knew was enough for him to be exiled from Vienna’s aristocracy. Despite performing with the Royal Philharmonic Society Orchestra at the age of 10 and being employed by the Prince of Wales, Bridgetower’s legacy is that of the young Black man Beethoven wrote a sonata for in 1804.

There’s your Black Beethoven.

Josh Gibson entered his prime as Babe Ruth faded, smacking 500-foot homers and reaching dizzying heights. While Americans worshipped white ballplayers-turned-servicemen like Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio at the height of WWII, Gibson spent years with the memory of his wife who died giving birth. He spent years as an alcoholic. He spent years knowing he was the best baseball player no one heard of, suffering a mental breakdown the same year he hit an unheard-of .466.

By the time he learned Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1945, Josh Gibson was a shell of his former self at just 35 years old. The jovial, barrel-chested young man was now brooding and out of shape. In 1946, his final season, Black fans abandoned Negro League games—Jackie needed their support badly. No one suspected Josh needed it just as much.

That winter, months after his final at-bat, Josh Gibson suffered a serious stroke and died. He was accompanied by several relatives who brought his awards and trophies into the room per his request. That was the greatest celebration of his legacy while he was alive.

There’s your Black Babe Ruth.

Some of humanity’s most accomplished people died silently, alone, and empty-handed because they were Black. And for every Bridgetower and Gibson that got to share their gifts without much credit or compensation, there are countless other Black people that weren’t allowed to get far enough to share what they had. But if looking back helps us move forward, let’s turn this clear hindsight into foresight.

Quickly, before Basquiat becomes the Black Banksy.

Before we trash the term “rapper” so badly that hip-hop dies in the hands of musicology PhDs.

Before white capitalists who pose as geniuses flee for Mars in 2065, and we’re left on Earth thinking we’re doomed despite being every bit as inventive, determined and capable—every bit as human—as they are.

Seriously, just give more Black folk their flowers while they’re with us.

For more thoughtful pop culture writing, subscribe to ATC’s newsletter!

UPDATE (12/17/2021): Edited capitalization of “White” racial identity to align with ATC’s editorial stance.

I love how leftists try to turn every famous white person into a black person. Just like ancient Egypt was black. LOL Babe Ruth WAS NOT BLACK. Get over it.

The insight we never knew we needed.