Once upon a time (the 1980s), A man from a faraway place came to America—no, not Prince Akeem, goofy—to study engineering. The man cared about art, but loved formulas. “Besides,” the man thought, “What good is knowing how to create if you can’t pass on the knowledge?“

One day (presumably), the man saw Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” on MTV.

“I want to create that,” exclaimed the man, “for my people.”

The man returned to the faraway place and began to design, to create. Not new software or devices, but culture, namely the products and the people who make them.

Today, South Korean cultural engineer Lee Soo-man watches Hallyu—the Korean wave of pop culture washing over the world—like Poseidon watches a tsunami from just beyond the horizon. The earthquake that caused this massive wave was his founding of SM Entertainment, the first of K-pop’s Big 3 labels.

BTS isn’t his group but they, along with every other K-pop group that has found an ounce of success outside of Korea, owe some of their good fortune to him. K-pop idols are born of the rigorous, detailed formula called Cultural Technology (CT). This formula is born of Lee Soo-man.

As impressive as his scientific approach to cultural product is, this brainchild of Lee’s mind was no virgin birth. And while the father is most accurately a group of entities, it makes this piece more pointed to name one man as the origin of CT: Michael Jackson. Not only the greatest entertainer of all time, but a Black American one. One who’s jaw-dropping package of visuals, dance moves and vocals inspired K-pop’s master blueprint.

What I’ve built up to is a point made by critical NCT stans and hip-hop forum dwellers alike: Black people godfathered K-pop.

This is not a verdict on K-pop. This piece is not a trial. But that truth, the influence of Black Americans on culture as far as South Korea, is an important one. Awareness of it helped realize the wild dreams of a wide-eyed Korean college kid. A global awareness of it could help stop the world’s constant robbery of its most culturally influential group of people. It could also forge a liberating bond between two of humanity’s most contrasting social realms.

Hyun Jin-young: K-pop’s Sacrificial Lamb

“Hyun’s committed practice of hip-hop in the Korean mainstream is the bedrock of today’s K-pop”

Before the supergroups and sonic collages that define today’s K-pop, South Korea’s entertainment industry required a seed from the West planted safely at home. This seed, of course, is hip-hop, straight from Black America’s soul. The man who first imported and nurtured this seed into the isolated peninsula’s consciousness was Hyun Jin-young.

In a Lee Soo-man speech at the 2020 World Knowledge Forum in Seoul, the first artist named by the K-pop mastermind is Hyun. As Lee briefly recounts his journey from college student in California to SM founder, he mentions Hyun as his “first iconic singer,” a star that burned brightly but flamed out quickly due to a “big scandal.” (Drug use is highly stigmatized in Korea, and Jin-young’s addiction issues spiraled for quite some time.)

Lee spends about 12 seconds explaining the importance of Jin-young. He then goes on to list a handful of successful SM groups including Shinee, f(X), H.O.T., Girl’s Generation, and NCT, developed through Lee’s patented formula, of course, Cultural Technology—much more on this later.

It’s not that Lee had to spend more time talking about Hyun. The speech was about the big picture, the belief that great content will soon be more important than great hardware or software. That CT will be more important than IT. But as asserted earlier, CT is born of Black American culture. For this reason, the person responsible for smuggling this Black life force into Korea deserves more attention.

Born Heo Hyeon-seok, Hyun Jin-young’s interest in music blossomed when his neighbors, Black American military kids, introduced him to rap music. While he grew into a proficient rapper, it was Hyun’s dancing—mastery of the Roger Rabbit, gotta love the 80s—that caught the eye of Lee Soo-man in 1989, then a singer in the twilight of his career sliding into the business side of the industry.

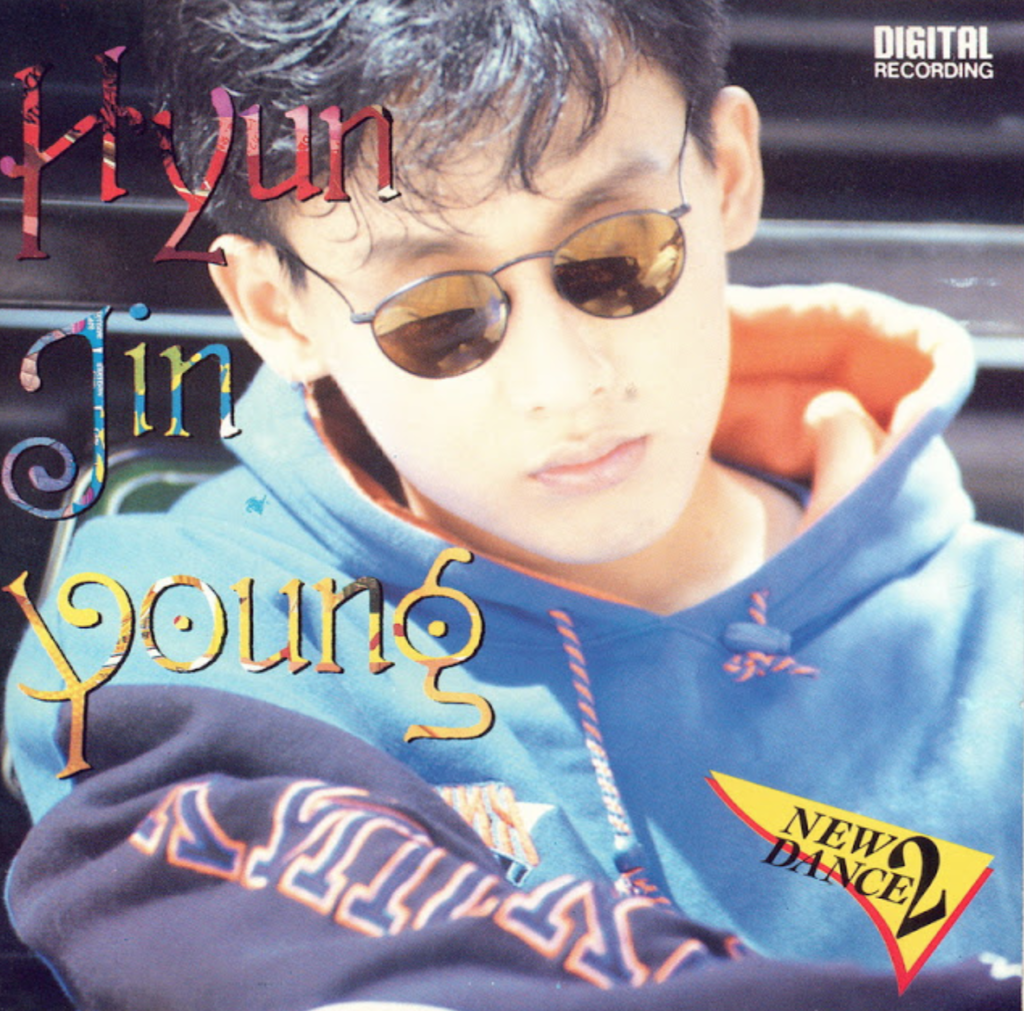

Hyun was Lee’s protégé for a year which included a stint as Lee’s backup dancer. With some choreography and vocal training under his belt, Hyun debuted in 1990 with the album New Dance 1 featuring his breakout hit “Sad Mannequin.” Hyun continued to shock the entire country for a few explosive years, showcasing his energetic moves, baggy pants, rapping and singing in televised performances.

Koreans likened him to Bobby Brown, LL Cool J, and other loosely-related Black American acts because Hyun was that bemusing to South Korean society. Despite the obvious groans from older Koreans, he gave the country their first successful model of Western cultural adoption.

It helped that the man was a dynamic talent. The consistency of his vocals and flows over three minutes of busy choreo makes this 1992 performance of “You’re in my unclear memory” (rough translation) hold its own against some of America’s beloved 90s boy bands and new jack swing acts:

Hyun Jin-young was the K-pop universe’s Big Bang, but many fans point to Seo Taiji and Boys as the first recognizable version of K-pop. The group’s blend of Western genres like rock and various forms of dance music was more palatable than Hyun’s diligent hip-hop/R&B focus.

Hip-hop still informed everything from their outfits to their verses and dancing, but the boy band feel and dilution of hip-hop sounds helped Seo Taiji and Boys eclipse Hyun once his career faltered. Amidst the success of their innovative genre-melding, it was the hip-hop infusion that really gave K-pop’s pioneering group its edge.

Seo Taiji and Boys loom large in K-pop history, but the group many credit for birthing K-pop is just the vibrant first sprout from the seed Hyun Jin-young planted.

Much like the Big Bang, Hyun’s success as Korea’s first major label hip-hop act spread a bunch of something into nothingness, allowing for countless phenomena to occur until moments like “Gangnam Style” and “Dynamite” made us ask, “How did we get here?”

Korean use of hip-hop and R&B is not perfect cultural exchange, but it’s more earnest than other popular cases of non-Black artists ripping off Black art (think Elvis and Miley). Much of this integrity, easily found in the craft of lead rappers and singers across K-pop groups, stems from Hyun.

Simply put, Hyun’s committed practice of hip-hop in the Korean mainstream is the bedrock of today’s K-pop. No hip-hop? No K-pop, and both Hyun Jin-young and Lee Soo-man knew this. Their awareness of this fact brought both Korean legends to Los Angeles for a music video not too long before Hyun’s second drug arrest tanked the opening act of his career. This American video shoot is something Lee today might call “glocalization.”

“Glocalization,” the Endgame of Cultural Technology

A Summer Day in L.A.

“Lee Soo-man knows K-pop starts with Black America”

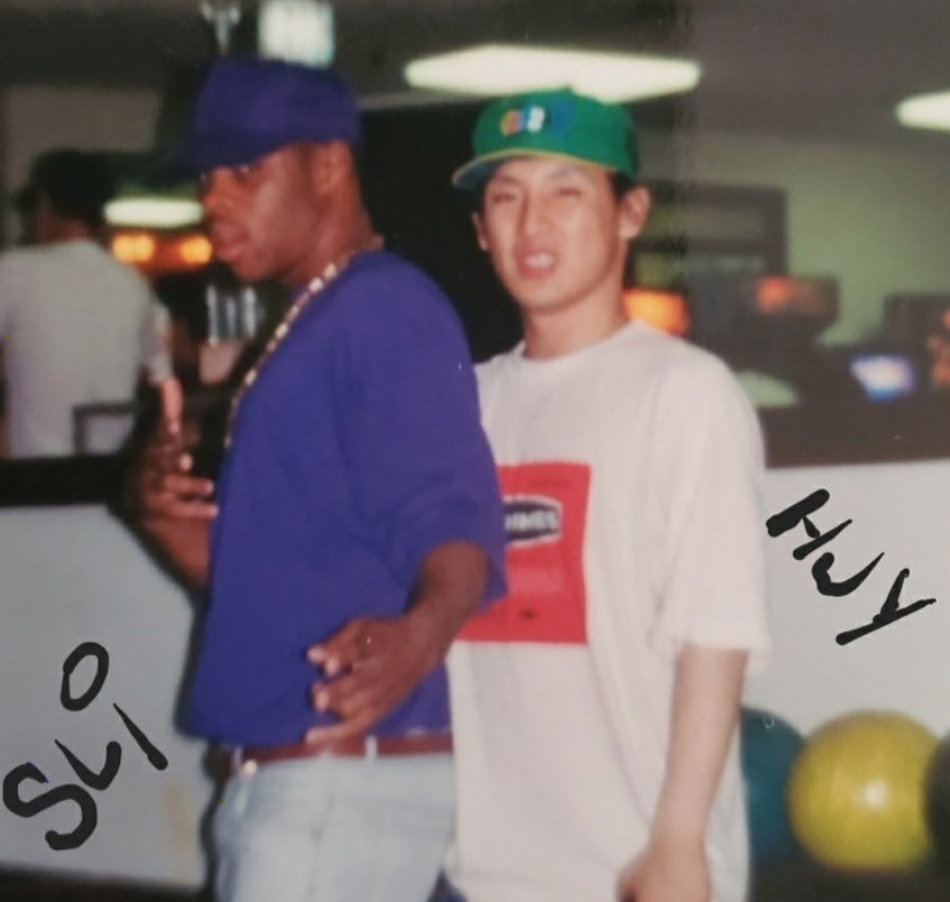

As Seo Taiji and Boys were on the way up, Hyun Jin-young was trying to stay afloat with a solid third album. In this gem of an LA Times article from May 1993, SM boss Lee Soo-man was simply known as Hyun’s promoter and manager. Lee is quoted as wanting to “get more of the American style” for Hyun’s next music video, so he went all out with the planning.

As reported by Gordon Dillow, this Spring 1993 video shoot in Los Angeles was an SM collaboration with Drop Dat Beat Productions, a charming little music production company in Hawthorne which was also a part-time ministry. Drop Dat Beat not only arranged and recorded some of Hyun’s third album, but they cast 20 amateur dancers (i.e. neighborhood kids) for Hyun’s video.

The day of the video shoot started with a chartered bus ride from Hawthorne to the intersection of Florence and Normandie, the notorious site where a white truck driver was beaten by four Black men on the first day of the L.A. riots the year before. Along with the police assault on Rodney King, the riots were fueled by the murder of Black teen Latasha Harlins, shot in the back of the head by Korean store owner Soon Ja Du who avoided jail time.

When asked about the significance of L.A.’s then-recent history, Hyun said, “It is sad place, but it happen a long time ago. We must now forget and shake hands.”

Once they finished their work at Florence and Normandie, Hyun shot some scenes with the youth dancers in front of the Crenshaw Wall murals. Hyun then hit Venice Beach to wrap up the shoot, even taking pictures with the legendary busker-on-skates Harry Perry.

On his choice to shoot in the United States, Lee Soo-man proclaimed “Hip-hop originated here, and that is why we wanted to make the third album and the music video here.” He also stated a desire to help create a “good relationship between black guys and the Korean community.”

Sadly, the video was never released. But even without visual proof, this near-mythical written history of K-pop’s origins makes two things very clear:

- Lee Soo-man knows K-pop starts with Black America

- Ground-level collaboration is crucial to Hallyu’s spread

Planning K-pop’s World Takeover

“What would K-pop execs be willing and able to do today once Black creatives claim their role in Hallyu’s rise?”

SM Entertainment did not coin the term “glocalization.” But they and the rest of K-pop’s major players value it more than anyone else in the world.

In an enlightening August 2019 interview with Billboard, SM A&R Chris Lee explained his company’s goals. No conversation about what SM does is complete without discussing CT, which Lee dives into detail about.

To start, Lee explains that CT is the manual from which all SM employees take their cues from. As discussed earlier, Lee Soo-man strongly believes culture should have a codified step-by-step process. This is SM’s ethos, using CT both as an instruction guide as well as a reference point from which to create new solutions as K-pop grows.

From there, Chris Lee highlights the three stages of the CT process: culture creation, expansion, and exportation. Stage 1, creation, is in itself a painstaking process where young talents are molded into well-rounded entertainers that don’t see the light of day until their label deems them ready. Stage 2, expansion, is the inclusion of artists outside of South Korea like EXO-M, the Chinese subgroup of EXO. Stage 3, exportation, is about making K-pop idols appealing beyond South Korea.

“We need to be there or be working with the people who are already there,” said Lee about markets outside of South Korea. Among these plans to globalize locally include marketing their most successful groups as brands of music rather than one act.

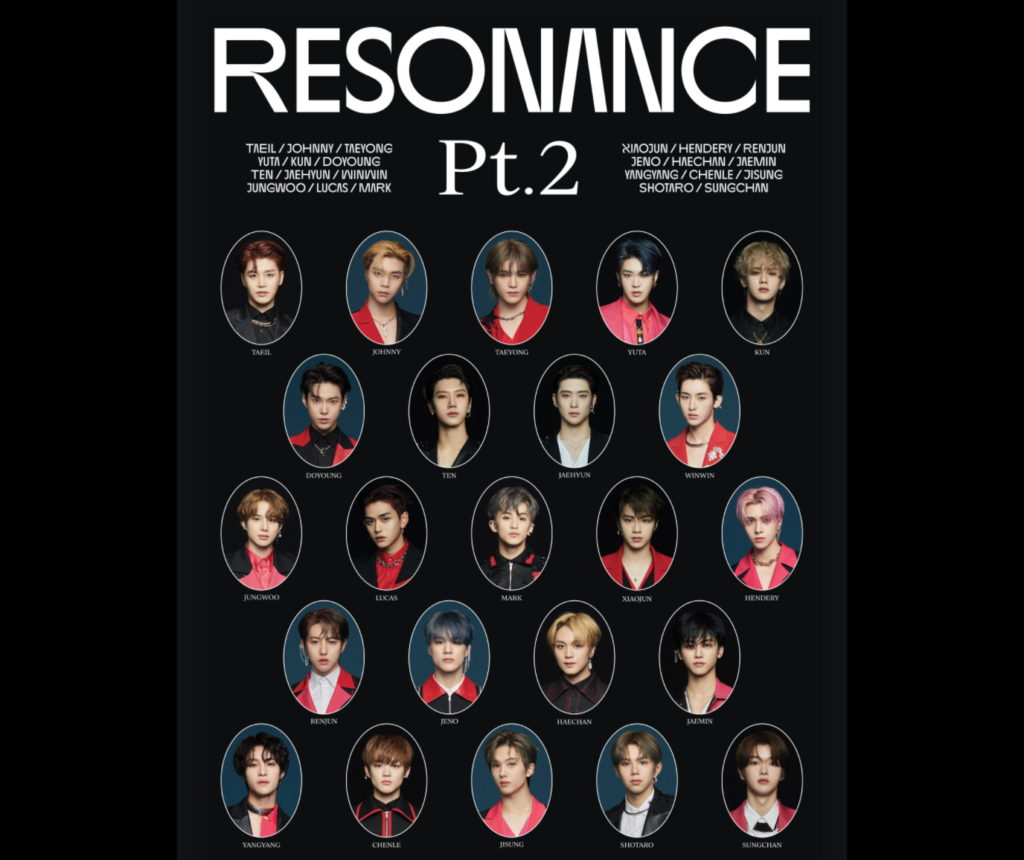

For example, the boy band NCT is not one band, rather, a group of bands under the NCT umbrella. As suggested by A&R Lee, exportation of the NCT brand would be the creation of a subgroup like NCT Thai or NCT Europe. These new subgroups would make NCT-brand content tailored for the markets they’re based in.

Clearly, getting local buy-in from markets around the world is crucial in CT’s 3rd stage. In order to achieve this nearly 30 years ago, SM was willing to work with a tiny production company that employed kids off the street in a predominantly Black part of L.A. What would K-pop execs be willing and able to do today once Black creatives claim their role in Hallyu’s rise?

What kind of partnerships could be arranged? What kind of advanced cultural product could bloom? What kind of justice could be delivered—economically, socially, and culturally—if Black people could co-pilot K-pop’s American journey? K-pop’s leaders actively involving Black fans and creatives could make beautiful use of the cultural power we all know Black consumers and creators have.

Does the global influence of Black Americans need open validation from K-pop? No. But Black people being enlisted to spearhead K-pop’s American foray would result in a reward much greater than clout from a research project. Black creatives—producers, designers, artists, product managers and so much more—stand to gain immense cultural and social capital, leadership roles that value Black expression, and perhaps diplomatic power greater than what the U.S. government has failed to cultivate via hip-hop.

Black involvement and leadership in K-pop’s American takeover is not an answer to all past and ongoing cultural theft. But it may be the start of one.

What Ever is a K-pop Stan To Do?

Is That a Fandom or an ARMY?

Stan culture among American acts is an array of chaotic personality cults. And while K-pop artists are literally called idols, there is much more of a method to the madness of K-pop stanhood.

This is important: if permanent space for healthy Black participation in K-pop is to exist, the culture’s biggest consumers need to care about this mission. As it turns out, there’s a decent foundation for this to happen.

K-pop, even more so than hip-hop and Western pop, is youth and women-driven. While the presence of 30-plus-year-old K-pop fans is surprisingly strong, fan activity is led by socially-conscious young women and girls who grew up on Twitter, BLM, and the Hunger Games series. Simply put, these fans have principles, social media skills, and time.

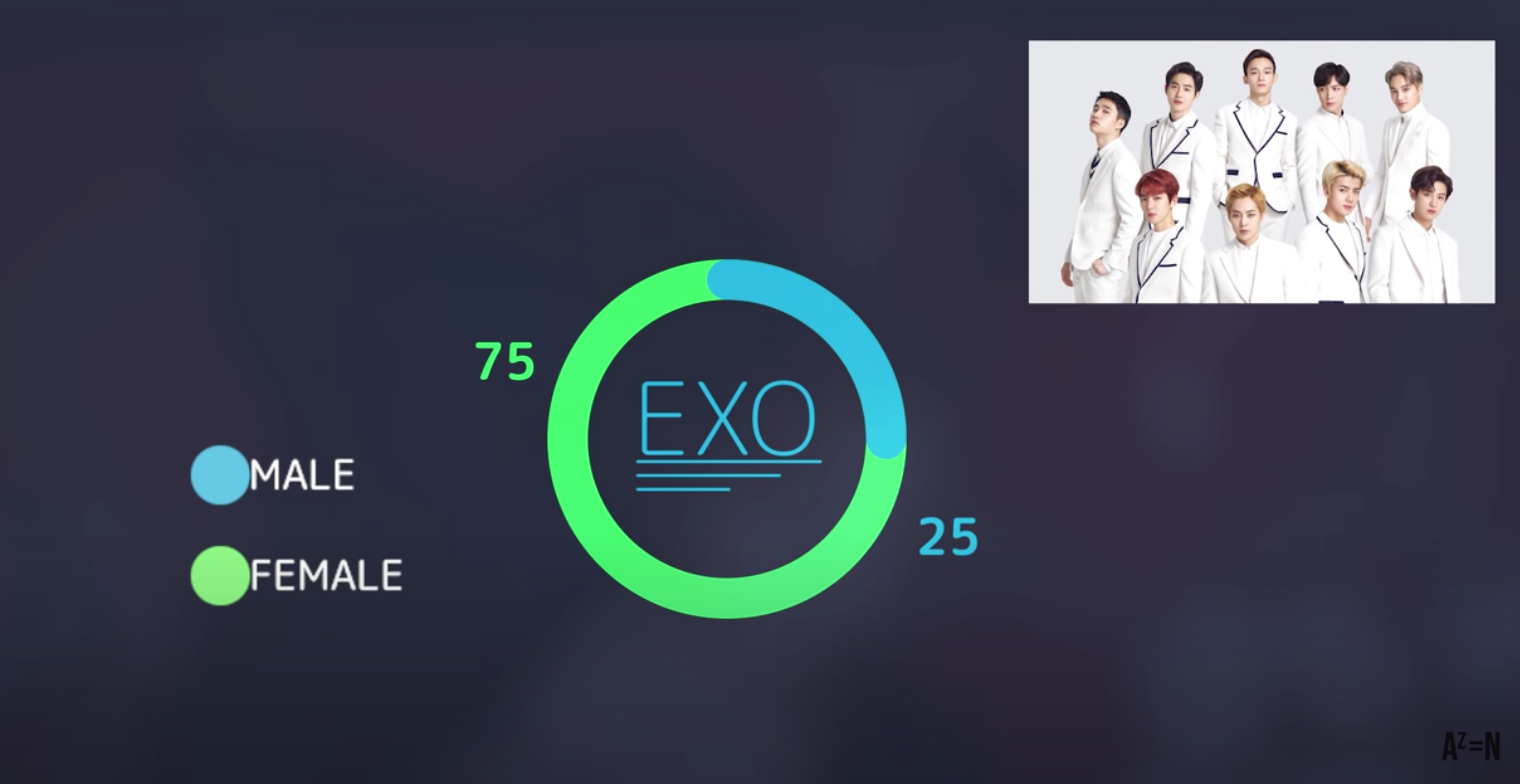

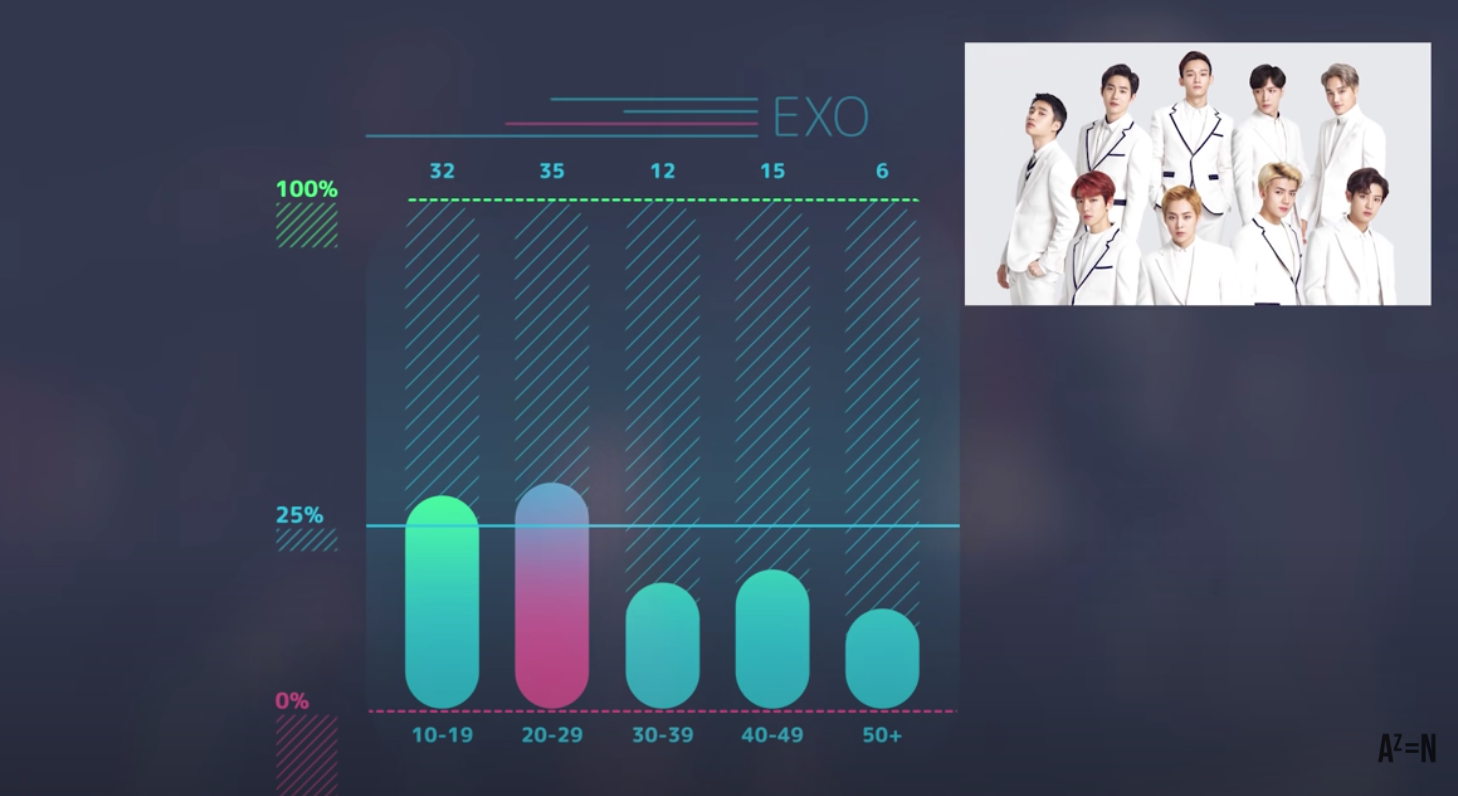

Pop culture has not seen a fan culture as large, diverse, and organized as K-pop fans. While big-picture demographic statistics are hard to come by, the biggest K-pop groups typically have fandoms 51-60 percent made up of 10 to 29-year-olds with a 70-30 female-to-male split. These young, mainly female K-pop fans are wildly effective when they choose to act for a cause.

Take BTS’ rise in the United States, for instance.

Billboard’s Social 50 chart, a relatively new chart tracking acts with the most online engagement, is dominated—I mean dominated—by BTS and their fans, the aptly named ARMY.

In February of this year, BTS set a record for the most weeks at #1 on this chart with 164. Then in October, BTS became the first act to spend 200 weeks at the top of the Social 50. Meaning they spent every single week at #1 between their record-breaking 164th week and their bar-raising 200th week.

In fact, BTS is enjoying their 179th consecutive week at #1 on the Social 50 as I write this, bringing their record-breaking total to 209 weeks and counting. Right behind them for the week of December 19, 2020 are fellow K-pop groups NCT and Treasure. Considering the Bangtan Boys haven’t left #1 since July 2017, they might have to get comfortable at 2nd and 3rd.

Any five-week run at the top of the Hot 100 or Billboard 200 charts is met with huge praise from American media outlets, like recent releases from Taylor Swift or Ariana Grande. Here, we’re talking about years of uninterrupted superiority as the most talked-about musical act in the world along with groundbreaking success on the more traditional charts.

K-pop fan commitment is so overwhelming it’s treated as a joke rather than an achievement. The value of such a unified, motivated, and huge group of people can’t be overlooked any longer.

Among other feats of coordinated online activity by K-pop fans:

- The takeovers of racist hashtags in the summer of 2020

- Mass ticket purchases to thin the crowd at Donald Trump’s inflammatory Tulsa rally

- $1 million donation from BTS to various racial justice groups matched by 34,000 fans in 24 hours

- Regularly topping Twitter’s Worldwide Trends list before they removed the feature this past Spring. Some of the most vocal critics, of course, were K-pop stan accounts

So, it’s clear K-pop fans are highly-trained digital minions itching to create change. How can this energy be honed to engage more Black people in Hallyu?

Supporting Black Folk Already in K-pop

“The simplest and first logical step would be to empower K-pop’s existing Black voices”

Of course, K-pop fandom isn’t perfect. It can be toxic, petty, and anti-Black despite the narrative of K-pop fans as model social justice warriors. Unsurprisingly, one of K-pop fandom’s ugliest aspects is targeted harassment of fans with unpopular critiques of an idol. Black K-pop fangirls are often the ones abused for their critical opinions, often call-outs of racist behavior and requests for idols to do better.

When K-pop fans across ages and racial groups band together to obstruct hate or push for justice, they’re praised. When Black women and girls in K-pop fandoms continue these missions on any given day, they may be labeled “antis” and pummeled with racist insults and death threats.

Since racial caste systems around the world are designed with dark-skinned women at the bottom, anti-Blackness and misogynoir are issues all non-Black people have to face within themselves and their peers. Defensiveness is common, and even socially-aware K-pop fans tend to harm Black women more often than they do other groups of people.

K-pop culture is largely driven by social perfectionism. There’s a lot invested into the belief that K-pop idols are fans’ “ideal selves” much like fans believe they are ideal supporters. Selling perfectionism and practicing capitalism makes the K-pop industry a shaky environment to fight for true anti-racism. Activism is inherently messy. The potential, however, is huge.

That being said, where is the starting point for a K-pop fan ready to impose their digital will and make Black America a greater part of Hallyu?

The simplest and first logical step would be to empower K-pop’s existing Black voices until race is a non-factor in the value of their concerns, opinions, and joy. Fans have done well to take songwriter Tiffany Red’s story of exploitation seriously, but building a culture of non-Black fans valuing Black people in K-pop must be intentional and persistent.

Coming up with a second step is futile since this first step has yet to be fully taken by any popular subculture in the world.

Now that K-pop, alongside hip-hop, drives global pop culture, the space available for Black people in K-pop depends on how avidly fans challenge each other to spot and undo racism within Hallyu. If K-pop fan culture can noticeably reduce its anti-Blackness, the possibilities are blown wide open.

Imagine a unified front in forcing accountability from K-pop labels by magnifying stories—like SM’s work with a company involved in China’s Uighur Muslim internment camps—for weeks on end.

Imagine the scope of sociopolitical engagement fans could pull off with more Black women co-leading battles against racism and other forms of bigotry worldwide.

Imagine Black K-pop idols and soloists being a normal sight! Just look at how drawn-out and controversial the debut of the first Black idol has been. How great would it be for a Black-Korean girl from Houston to debut with Aespa America, or some other hypothetical subgroup, in 2030 without the headline being about her race?

Even if Black folk had nothing to do with the growth of K-pop, fans would be remiss to not practice what their idols—particularly BTS—regularly preach. The Map of the Soul album series discusses introspection and facing one’s inner darkness a lot. When it comes to pop culture, that creeping darkness is often racism.

It’s so easy for the world’s collective mind to take artistic jewels from Black folk without confronting the cruel human-made conditions that inspired much of that art. In K-pop fans, there is hope that a large-enough group of people might make the world confront these truths after all.

It’s difficult to see how any of this matters. And even if you do see what’s at stake here, it’s harder yet to imagine any meaningful change in the status of Black people coming from teens with fancams saved on their laptop. But if love for Black expression has brought K-pop so high, who’s to say that same love, plus an organized long-term movement, can’t bring a new generation of Black Americans with it?