I actually had rather high hopes for Beyoncé’s new album.

Lead single “Break My Soul,” in all of its relentless, Big Freedia and Robin S.-sampling thumpery, piqued my interest big time; not to mention its opening verse about falling in love and quitting a job after being overworked. To sum up, the song more or less captured my life and mood up to the point of its release.

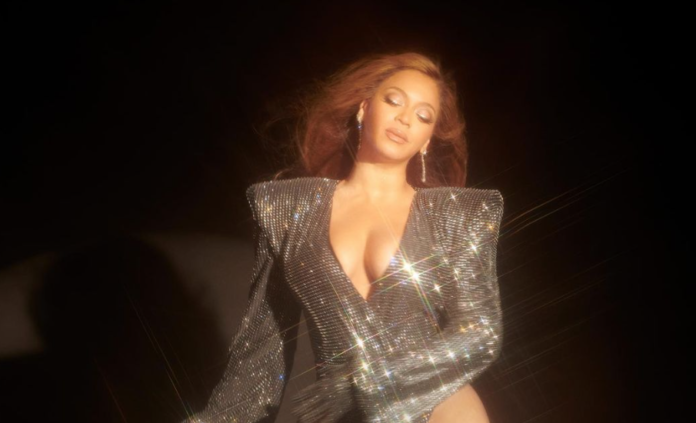

“Soaring vocals and fierce beats combine and in a split second I’m transported back to the clubs of my youth,” writes British Vogue editor Edward Enninful in his accompanying essay for the singer’s fashion spread. “It’s music I love to my core. Music that makes you rise, that turns your mind to cultures and subcultures, to our people past and present, music that will unite so many on the dance floor, music that touches your soul.”

That’s a big sell for an imminent release. And so, while having “Break My Soul” on repeat, I was awaiting the arrival of Renaissance quite excitedly, especially considering it was Beyoncé’s first solo release in over a decade to arrive with an advance notice. Once the album dropped, I hurriedly pressed play … only to keep skipping until the very end after just a couple of tracks.

Renaissance kicks off promisingly enough with the formless and percussive “I’m That Girl” (which, in a way, reminds me of former bandmate Kelly Rowland’s 2011 album opener “I’m Dat Chick”), before seguing into the equally formless and even more percussive “Cozy.” And that’s where things begin to go downhill, for the most part. (Also, yes, “swaggy” is as cringeworthy coming from Beyoncé as it is from Justin Bieber.)

It’s always been difficult for me to fully connect with, let alone admire, Beyoncé’s persona, either on or off record. To many heterosexual women and gay men, she might be a symbol of class, glam, confidence and yes, perfection. To me, she’s a reminder of that type-A, overachieving, teacher’s pet classmate with the overly shiny and polished veneer … and nothing else.

***

For an intergenerational act like Beyoncé, it’s too easy to simply latch on to her most current incarnation, especially now that she’s an incontestable, untouchable, nearly God-like pop culture figure. The problem is I grew up with Beyoncé 1.0, one-fourth of a girl group in a sea of girl groups, who had the managerial and artistic backing of her entire family. She might have sung all the leads (and done a great job with it), but she always did lack the grit and the sass that virtually any of her other fellow group members possessed but had to keep under wraps to maintain the faultless pop star façade.

20 years into her solo career, it doesn’t feel to me like Beyoncé has even remotely shaken off that image; she simply went from “the perfect girl” to “the perfect bitch.” There’s usually a sense of remove, or even sometimes disconnect, between her singing and whatever musical backdrop she’s draped in, especially whenever she stylistically shifts beyond R&B (modern or traditional) and pop balladry and tries to get down with the young’uns. It’s almost like no matter the material, she must sound pageant-like — flawless, to quote her own hit — at all costs, and this is the issue that plagues the bulk of Renaissance.

As a listener, you expect a so-advertised dance album to have a cathartic, euphoria-inducing, or even transcendental impact. At the very least, you want it to tickle and galvanize your senses. Renaissance, on the other hand, is more or less the exact opposite of that; it’s akin to watching the aforementioned classmate making an impeccable presentation in front of the class that you know they studied days and nights for … except that you find it hard to fully sink your teeth into it; for all of its boastfulness and on-paper excellence, there’s something about it that keeps you at bay, unmoved and even apathetic. In other words, it’s underwhelming.

Over the course of Renaissance, Beyoncé’s vocals are placed so on top of the mix, perhaps to maintain a regal, authoritative disposition — her go-to disposition — at the expense of being engaged with, and in turn convincingly selling, her material. The beats might be sleek, the rhythm stylish, the production high-end, but for a groove-heavy work, you don’t quite get the sense that she’s in the groove; for most of it, she sort of just hovers above or skirts around it, like a too-cool-for-school spectator.

Contrast this to her past outings: in Destiny’s Child’s “No, No, No” or “Lose My Breath,” for instance, she rides the propulsive rhythmic turns with aplomb; in her own “Ring The Alarm” or “Get Me Bodied,” she lets loose and unhinges herself vocally to exhilarating effect. In Renaissance’s dancehall-inflected “Heated,” one of the album’s more decent cuts (and a direct homage to her late gay uncle to whom she dedicates the album), she attempts to pull a similar trick to less than affecting results, while its subsequent track “Thique,” although featuring some of her most on-point vocals in the album, sort of just meanders and loses steam quickly despite its short running time.

I’m still not entirely certain whether Beyoncé’s recent proclivity for abstract, formless compositions — a hodgepodge method born out of songwriting camps where memeable quips take precedence over memorable hooks — is an actual marker of genius or just the media’s way of hyping up mediocrity. (After all, Tina Turner remains the undisputed Queen of Rock and Brandy is the Vocal Bible despite having next to no songwriting credit in their respective discographies.) I believe that at the end of the day, the greatness of music can be measured by how it moves you or makes you feel. Renaissance, for all of its noble intents and purposes, ultimately doesn’t quite move me or impart any feeling to me, not even in a cerebral way.

Much like its main performer’s curatorial approach, at its best, Renaissance is a funky aural backdrop that grabs your attention for a few fleeting seconds every now and then but doesn’t necessarily have a grip on you or take you to the heavens the way that “Break My Soul” initially hinted at. For a second, I was actually hoping that the album would be a full-on early ‘90s diva house excursion in the vein of Martha Wash, CeCe Peniston, or Crystal Waters; if anyone in mainstream music can, or should, emulate that type of sound, Beyoncé is definitely that girl.

Instead, listening to Renaissance left me wondering: what does Beyoncé actually ask of her listeners? To sing along in bodily ecstasy with her? To join in on the celebration of niche Black cultures and sounds through the ages? To have them marvel at how hot she looks or how lavish her lifestyle is? If anything, it actually made me appreciate Lizzo’s earnest bawdiness — she does make her listeners feel good as hell. Her Black, fat, vegan joy is infectious.

***

While Beyoncé’s work ethic and constant flow of releases are indeed admirable, her monopoly as not only the leading but the sole Black female artist with indubitable cultural clout can, in fact, be dangerous

I was reminded of what Kelela said prior to the release of her 2017 debut LP, Take Me Apart: “I was mad at myself for not writing about [my experience as a Black woman in the record’s lyrics],” she confesses. “But I came to the conclusion that since I’m a Black woman, nothing that I make could ever exist outside of that experience.” That resolution is so palpable throughout Take Me Apart, which deftly blends R&B and electronica in an endlessly inventive and arresting manner.

What’s ironic is Beyoncé already pulled it off swimmingly before: her 2006 sophomore set B’Day bumps, grinds, struts, and grooves over the course of its first 8 tracks alone — half of Renaissance’s 16-track suite — to better impact and aural satisfaction. To this day, I always say that B’Day is the quintessential Beyoncé album, the one that succinctly encapsulates who and what she is about as a singer and recording artist before her later-day artsy-fartsy turn.

The shift in paradigm to Beyoncé’s public image didn’t begin in earnest until roughly a decade ago. By the time her 2013 self-titled effort came out, the stars aligned in her favor: sure, the surprise release and the visual album elements factored in too, but this was also a time when digital downloads swiftly replaced CD sales and most of Beyoncé’s turn-of-the-millennium contemporaries (e.g. Alicia Keys, Mary J. Blige, Mariah Carey) were by and large out of fashion. In their places were the likes of Katy Perry, Rihanna, and Miley Cyrus, the public consensus on whom was quite clean-cut: they were not powerhouses, they were scantily clad provocateurs who relied on shock value rather than artistry.

Stack them up against Beyoncé’s old-school perfectionism, her fierce and elaborate stage act, and her increasingly more discreet and cryptic off-stage shtick — never mind that she has been scantily clad for most of her career herself — then you have yourself the perfect recipe for the Beyonce 2.0 phenomenon.

While Beyoncé’s work ethic and constant flow of releases are indeed admirable, her monopoly as not only the leading but the sole Black female artist with indubitable cultural clout (especially as Rihanna, the only other Black female artist in recent times to match her clout, is currently more occupied with popping out lip kits than smash hits) can, in fact, be dangerous. I grew up during periods where so many Black female artists ruled the charts and the airwaves, and with a wide range of stylistic options too: for every Alicia Keys, there was an Ashanti or a Ciara; for every Mary J. Blige, there was an India Arie or a Keyshia Cole. Without having to invoke them, variety and diversity were already in place.

As our attention spans are ever so fragmented and the new crop of R&B acts are grappling for relevancy, what we end up having is a bunch of semi-popular acts existing in their own small pockets of fame, never quite reaching cultural ubiquity the way that they perhaps would have in a different era. I remember when SZA became the most nominated female artist at the 2018 Grammy Awards, an acquaintance — a Beyoncé stan to boot — was downright dismissive: “I don’t know who that is. Never heard of her music.”

This is of course good news for Beyoncé, judging by all the glowing reception tossed her way in the wake of Renaissance’s release. It’s unfortunate, however, that in the so-called age of “visibility” and “representation,” the culture somehow decided that only one artist can be the ultimate representative of Black female artistry and excellence; worse still, if you dare criticize her or her work, you must be anti-Black and anti-female and so on and so forth. But what if you’re just anti-mediocrity?

Similar to Lizzo, a huge factor of why the general public and media have been so protective to the point of being unnecessarily defensive of Beyoncé has a lot to do with what she represents: Blackness, but not too Black (her own father admitted to as much); empowered, but still commodifying it; FEMINIST, yet ever so subservient. In short, she’s cult of personality personified.

Case in point: my critique of Beyoncé losing Album of the Year at the Grammys to Adele. Did she deserve the damn award? Absolutely. If Taylor Swift managed to notch up three wins in that category alone for even more mediocre work, then Beyoncé sure as hell deserved that stupid trophy. Heck, she is officially the most awarded female artist in the history of the Grammys as we speak! But at its core, it was less to do with Beyoncé herself and more to do with the masses crying foul over her loss for tokenistic and performative purposes.

I find it amusing to compare the reviews on Renaissance versus Kelis’ 2010 opus Flesh Tone, virtually the first full-length release by a modern U.S. R&B act to dive deep into the heady, sweaty realm of dance and electronica. Here we have two cultural icons: one widely beloved and heralded, the other frustratingly undersung yet incontestably influential. Despite Flesh Tone‘s soulful throatiness and poignant, life-affirming floorfillers, the critical (and naturally commercial) reception to it was a lot more muted simply because it was … Kelis. And yet, guess which album still makes one want — nah, keen — to emancipate themselves?

Beyoncé is free to partake in her own cultural heritage, regardless of her actual proximity to aspects of it showcased in Renaissance. And if in the process the album exposes a litany of Black pioneers and/or pioneering Black arts to factions of modern society unbothered to go beyond the mainstream pop bubble, then more power to her. Unfortunately, to these ears, much of Renaissance like Beyoncé herself comes across as posturing, the idea of a high-brow work as masterminded through the lens of a wealthy pop juggernaut. Eventually, the album’s overall execution falls short of its initial promise of a full-on dance record and doesn’t quite feel lived in even as she tries to cozy up to the working class and queer communities. But props to her for trying, I guess.

Stream Aluna’s Renaissance, y’all.

[…] Source link […]

Correction: Rennaissance is definitely more than “funky aural backdrop” music. I don’t know if this got posted the first time.

Yes, Renaissance has definitely grown on me over time – I’ve warmed up to it a lot nearly two years later, especially after having seen the film. But this piece reflected where I was at with the album then and it spoke truthfully to my mental state as a listener at the point of its writing. I totally agree re: Plastic Off The Sofa, Virgo’s Groove and Break My Soul, though. Again, the new piece I’m working on, coming out soon here on ATC, will touch upon this too, so stay tuned!

This review seems for an evaluation of Beyonce as a cultural brand than a review of the album. First of all, I don’t think the writer accurately characterizes Beyonce’s place in the cultural landscape. By no means is she “incontestable” or “untouchable” to anyone except her biggest fans. Beyonce does get a lot of hate and criticism just like any other pop star in the history of the music industry. She has her defenders and has her detractors. This article is proof that Beyonce isn’t considered “incontestable” or “untouchable”.

Anyways, to the album. Renaissance, in my opinion, is definitely more “funky aural backdrop” music. Renaissance isn’t a classic album like Thriller or Purple Rain; however, I do think it is a solid album with some really great tracks. “Plastic of The Sofa” is truly one of the greatest soul records of the last decade or so and “Virgo’s Groove” is a fantastic disco track. “Break My Soul” was a hit. “Cuff It” is a fantastic track except for the unnecessary cursing in the lyrics. The rest of the tracks are okay, but there are definitely some great songs in this album. A solid addition to Beyonce’s catalogue.

Furthermore, I agree with your point that there needs to be more black female artists who are propped up by the industry. I think it is a shame that Beyonce and Rihanna are the only ones who are promoted. I would like to hear from the writer.

Hey, thanks a lot for your comment! Appreciate it. Wild that this article is gaining traction nearly two years on, haha.

Re: Beyoncé being incontestable/untouchable, I can absolutely see it from your point of view as a reader/consumer but I had the mainstream/liberal media in mind when writing that bit, especially during the Lemonade era, her losing Album of the Year at the 2017 Grammys and all that jazz – there was definitely a time when it felt like not buying into her stuff was seen as being anti-Black or whatever, at least from my point of view, and it felt rather ridiculous to me, esp concerning the other point I made about the media, and by extension the general public, not reserving that same energy for other Black female artists. I’ve been a fan of many Black female artists my entire life, I grew up listening to tons of them, having multiple of them in the mainstream, at the top of the charts, what have you… then suddenly it was just her and Rihanna. It felt so jarring to me and it left me feeling frustrated as a music fan.

But of course, it’s not Beyoncé’s fault, it’s on the industry at large and I probably didn’t articulate it as thoroughly as I should have here that it ended up coming across as putting all these Black female artists against one another. I do have a piece coming up that I believe articulates this perspective better, so look out for that one! 🙂