Music streaming records get broken every full moon these days, which makes the novelty of album-equivalent units (AEUs) hard to judge. And unless you care enough to do some research, these seemingly made-up numbers—in some cases actual made-up numbers—next to the names of obnoxiously famous artists won’t help you understand the value of an RIAA platinum plaque in today’s world.

But this article will.

My first look into the streaming-is-cheating myth was in a piece comparing the commercial successes of Drake to Lil Wayne and Jay-Z. I still stand by the conclusions in that piece, but several details about the AEU formulas used by Billboard and the RIAA need to be cleared up and expanded upon.

The Formulas

It is true that 1,500 streams used to equal 1 album sale on the Billboard charts and 150 streams equaled 1 sale of a single…until 2018. (I would have linked to Billboard directly, but they now require Pro access. Womp.)

In May of that year, Billboard announced levels to this shit: streams from premium members of digital music platforms were given more weight, and streams from free users of digital music platforms became nearly three times less valuable than they were in pre-2018 sales counts.

Today, Billboard counts 1,250 premium member streams as an AEU and it takes 3,750 ad-supported (i.e. free) streams to earn the same. Meanwhile, the RIAA has held onto the 1,500 streams per album rate for their gold and platinum certifications. It seems like 150 streams still equals the sale of a single according to both authorities.

People who don’t pay to stream still contribute to sales. How?

Streaming platforms pay artists with money received from subscription fees and advertisers. Below is a breakdown from Spotify reps of their own payout process:

(UPDATE 7/22/2020: the video has been removed from Spotify’s YouTube account. Here’s a highly-informative breakdown of the payment process from Record Player Pros though)

Perhaps you are not giving Post Malone a dime when you stream those two guilty-pleasure Beerbongs & Bentleys tracks on your work commute playlist. But the advertisers who invade your mind in between the hundreds of times “Psycho” and “Better Now” play in your car are paying. Not all of what they pay goes directly into Malone’s pockets, but the attention you give to his music creates the sonic ad space in your car purchased by advertisers. So yes, free streams generate money.

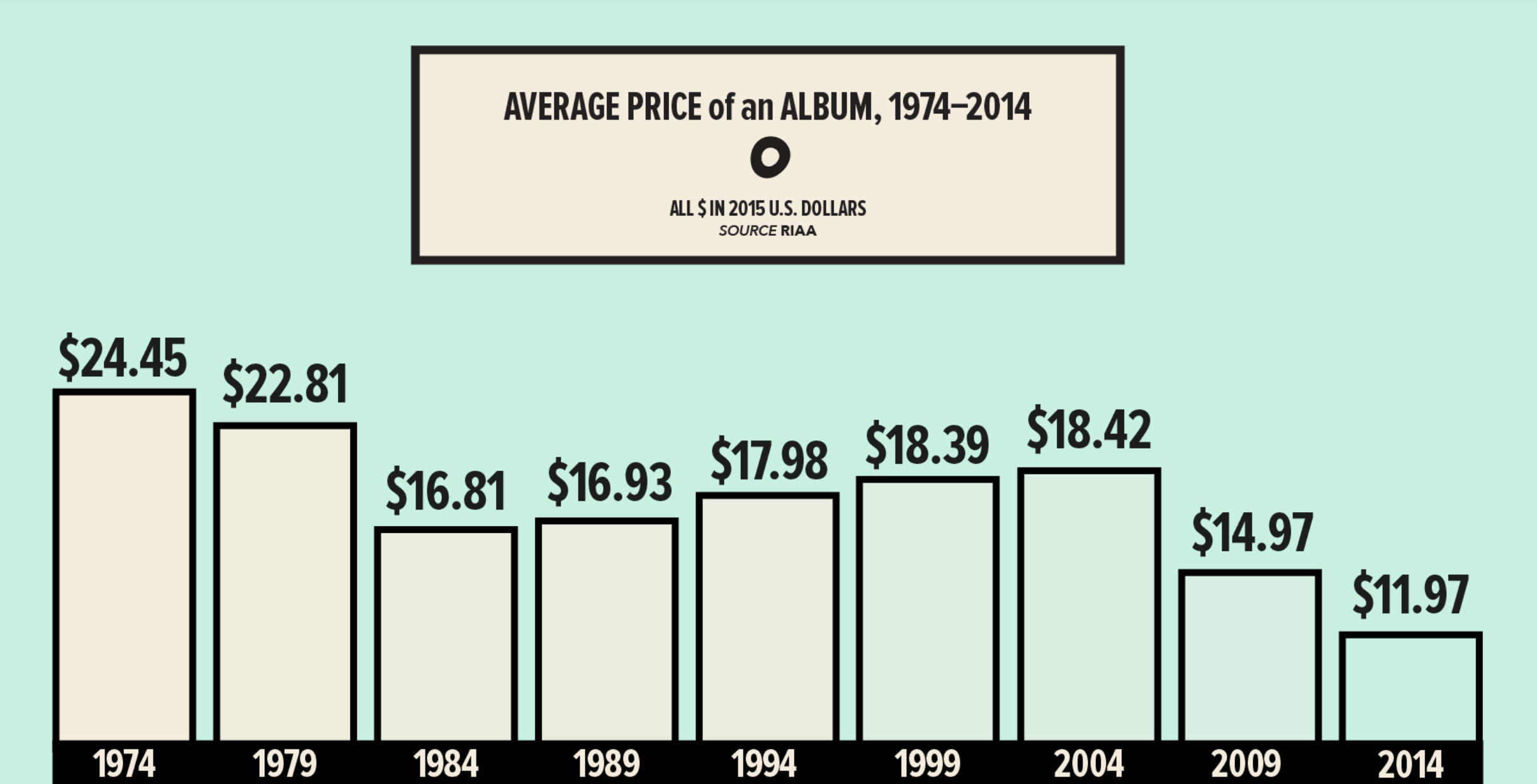

Even at the lowest per-stream payout rate Spotify claimed to offer in 2013—$0.006, or six-tenths of a cent—an AEU of 1,500 streams would mean $9 worth of streams qualified as an album sale. At Spotify’s highest per-stream rate of $0.0084, 1,500 streams would equate to an album that cost $12.60. According to Spotify in 2013, payout rates increase as more paying subscribers join the platform. These 2019 revenue estimates using 2013 rates are likely modest. For perspective, the average price of an album in 2014 was $11.97.

Using the new Billboard formula, the monetary value of an AEU significantly outweighs a pure sale (digital or physical purchase) of an album. At the low-end of Spotify’s 2013 payout rate, 3,750 ad-supported streams is $22.50 in generated revenue. This competes with even the highest average album prices of the 1970s.

So back to your casual streaming of Post Malone singles: as far as the economic impact goes, you may as well have bought a copy of Beerbongs & Bentleys at Target every few months. To put it plainly, streams are just as legit as sales.

Even if we assert the unverified yet plausible insider claim that 3-4 percent of global streams are fake, Ariana Grande’s “thank u, next” being streamed 100 million times in 11 days is largely not the doing of bots. Neither is the 1 billion streams Scorpion received in its first week. Some artists have the power to make millions of people devour a record. It’s been like that since Al Jolson when fucking sheet music was flying off the shelves…or wherever people bought sheet music.

In the past, the valuation of a fan’s record consumption was measured strictly through one-time upfront payments. In today’s game, every little bite has a value placed on it. This is different, but not necessarily more or less fair to pre-streaming artists. And if there was an argument to be made about fairness, AEUs are actually balancing the scales for artists of this millennium, not tipping them.

Revenue from U.S. music sales and licensing dropped by more than half between the 1990s and the 2000s decades, and pure sales are endangered, especially in hip-hop where #1 albums attribute a healthy majority of their sales to streaming. Contrary to popular belief, making AEUs official to accommodate streaming is a response to an era of dying sales, not a cause.

Streaming in music is like the 3-point line in the NBA. The advent of it has made the game faster and more accessible to different players. But to this day, you can count on one hand the players who have approached Wilt or Jordan-level seasons of scoring. Also, only a handful of players have built legendary careers using the game’s new rules as the foundation. Likewise, it’s unlikely artists setting streaming records today will have an album that outsells Thriller, and only a couple of artists will enter Beatles/Michael/Elvis territory through streaming dominance.

There’s plenty to criticize the streaming revolution for—rushed consumption of albums, bloated tracklists, a greater obsession with numbers—but it hasn’t cheapened the value of milestone commercial achievements. Despite the petty games some A-list artists play in pursuit of sales, platinum plaques and #1 songs and albums are still hard to come by. Besides, none of today’s shifts in the music biz are that original: Sinatra fans in the 1950s crying about radio killing the jukebox are today’s ’90s babies complaining about new-age artists staying relevant with barely any pure sales.

More important than reminding music streaming critics that bots don’t create legends is this: streaming lowers the barriers of entry in a historically exclusive industry. The music business will always be shady, but streaming allows the rapper with a fifty dollar mic and a budget for beat leases to have their music available in the same places as their favorite artists. Also, that DIY rapper can make money and possibly fund a mini-tour, their next project, or just feel validated by it.

Streaming is not the Devil, so get over it. And don’t leave a link to the TIDAL fake stream scandal in the comments, we know.

UPDATE 9/7/2021: Edited for tone

[…] of an album coming soon. Liberation debuted at number six on the Billboard Hot 100 with 68,000 album equivalents (AEU), Aguilera’s lowest sales in its twenty-year history of music release. The album sold […]

Funny how you ignore the key difference between now and when music was bought…RADIO. Everyone used to listen to radio and the teens who would devour Ariana Grande now listened to Mariah Carey, Britney Spears and Avril Lavigne daily at least via top 20 song lists on FM stations. But you know what? Those weren’t counted. And you also omitted SINGLES which were a huge part of sales for close to a hundred years. Singles were just on-demand top 20 hits for the listeners who couldn’t wait til tomorrow to hear it again and who likely lacked money for a full album. Those were tracked separately from album sales for decades and decades also. ……..so no, Ariana Grande being listened to 100 million times in 11 days is not impressive when NSync had first week sales of 2 million albums and hundreds of millions of uncounted listens worldwide via radio. Whatever exists now in the music industry is a pale imitation of what it used to be. Is Drake the #1 best selling black musician in decades? No. Is he likely on par with Outkast in terms of units sold, had him and his fans been around 20 years earlier? Probably. But the point is, a small percentage of people even listen to music like they used to, and that is proven by anemic physical album sales, inability for premium stream users to specify how their revenue gets shared (vs giving each track they listened to roughly .0006 cents) and stagnate concert attendance (when population growth is factored in).

Hi Scott,

Artists today also get hundreds of millions of radio impressions. In 2017, for instance, “Wild Thoughts” by DJ Khaled and Rihanna received 137 million impressions in its first week out. They still don’t count toward record sales, so don’t worry, pre-streaming artists are not being cheated out of record sales in this way.

In the total record sales numbers of pre-streaming acts such as Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Prince, those are numbers that include album, music video, and single sales. Each unit of music is considered a record, so no, pre-streaming artists are not being cheated in that way either.

Yes, radio was the leading platform of music discovery in the era of peak physical music sales. Napster and related file-sharing platforms are regularly cited by experts as the watershed moment changing music listeners’ behaviors and values around the accessibility of music. These changes have made it easier for people to discover and create new music, but harder for individual acts to sell. You rightly point out today’s weak physical sales and stagnant concert attendance, yet insist on claiming record sales are easier to come by in an admittedly more disengaged fan culture. How?

Fourteen of the 20 albums that have sold 1 million or more copies first week in the United States were released before 2010. If, even with streaming, artists not named Taylor Swift struggle to reach NSYNC/Britney/Eminem heights, what exactly is so unfair about music streaming? Is it flawed and, as you say, a pale imitation of what music listening used to be? Absolutely! But it hardly inflates the commercial accomplishments of today’s artists.

Thank you for reading and commenting.